Yachting World

- Digital Edition

Inside the Royal Yacht Squadron – we get a rare view of this most exclusive club

- Belinda Bird

- May 18, 2015

Sarah Norbury jumps at a rare chance to see inside the Royal Yacht Squadron, that unique and intriguing yacht club at the centre of Cowes, in its 200th anniversary year

Photo: Paul Wyeth

The Royal Yacht Squadron’s Castle clubhouse is best known to most sailors as the centre of the action at Cowes Week. Puffs of smoke in the aftermath of the bangs waft across the water towards the fleets of yachts, their crews’ faces pinched with concentration as they plan their beat up the rocky Island shore.

No first-timer to Cowes Week can fail to be awestruck by the Castle. Competitors mill around before their starts, staring at the flags and course-boards, getting a sight down the startline straight into the windows.

Looking is as near as most sailors ever get to this most aristocratic of clubs. Members will repair to the Squadron after racing, taking tea on the lawn, before entering the Castle for cocktails before a party or the fabulous Squadron Ball, but for the rest, the Castle itself, built by Henry VIII to repel the French, is a visual symbol of the club’s exclusivity.

The Platform, from where Cowes Week starts are signalled. Photo: YPS/Boat Exclusive

The most prestigious club in Britain, possibly the world, is wreathed in mystique. The only way to join this club of Kings, Lords, Hons and Sirs is to be invited by a member and be subject to a secret ballot. The fact that the membership list reads like Debretts is an indication of most sailors’ chances of being invited.

It’s said that wealthy tea merchant Sir Thomas Lipton was blackballed for being ‘in trade’, which is why his 1898 bid for the America’s Cup was sponsored by the Royal Ulster YC. He was allowed in eventually, but died just two years later so scarcely had time to enjoy the Castle’s delights.

Some accept a blackballing with grace, others kick up a stink, like the owner of a 150-ton schooner who, the story goes, sent a message to the club that he was anchored within close range and would commence shelling unless he received a personal apology from Percy Shelley, son of the famous poet, who had blackballed him.

Flying the white ensign

The appeal of being a member is obvious. Who wouldn’t want to fly the white ensign from their stern? The Squadron is the only yacht club with a Royal Navy warrant to do so, granted in 1829. And who wouldn’t want to walk boldly in to meet and drink with the great and the good?

I asked the current commodore, the Hon Christopher Sharples why, when a number of royal clubs are struggling to find new members, the Squadron has a healthy waiting list. “It’s a very fine club,” he responded. “People enjoy the standards and the tremendous history. Members treat the Castle as a much-loved country home.”

RYS commodore, the Hon Christopher Sharples

Originally named The Yacht Club, it was founded on 1 June 1815 by a group of 42 gentleman yachting enthusiasts. Five years later, member King George IV conferred the Royal in the club’s title and in 1833 King William IV renamed the club the Royal Yacht Squadron. Members met in the Thatched House Tavern in St James’s, London, and in Cowes twice a year for dinner.

Today there are 535 members and dinner is served in the magnificent Members’ Dining Room, under the painted gaze of illustrious past admirals and commodores. The room is adorned with silver trophies and scenes of the high seas, and waiters bring course after course from the kitchens and wine cellars below. There are bedrooms for overnight stays, a room for members to keep their ‘mess kit’ or black tie, which is required dress on Saturday nights, and even gun lockers for shooting parties.

But sailing is the club’s raision d’être and neither a title nor a fortune are a guarantee of entry. The club professes that “any gentleman or lady actively interested in yachting” is eligible for nomination.

The Library, a peaceful sanctuary as well as an important archive. Photo: YPS/Boat Exclusive

The Squadron was where yacht racing was born. In the early 1800s the aristocracy came to Cowes to socialise and cruise in their boats. The first races were duels between the yachts of the day, then rules for fleet racing were drawn up. The first club regatta, later to become Cowes Week, was in 1826. For more than a century the reigning monarch would be there to present the King’s or Queen’s trophy.

Some of history’s greatest yachtsmen are on the Squadron’s membership roll: Sir Thomas Sopwith, John Illingworth, Sir Francis Chichester, Sir Alec Rose, Sir Robin Knox-Johnston. Ties with the Navy are strong and some of British maritime history’s most famous names have been Squadron members, not least Nelson’s vice-admiral Sir Thomas Masterman Hardy who commanded HMS Victory at the Battle of Trafalgar, Admiral Lord Cochrane who was the inspriation for C.S. Forester’s Hornblower novels and Admiral Sir Jeremy Black, captain of the aircraft carrier HMS Invincible during the Falklands War.

The public’s more usual view

Perhaps the club is still best known around the world for hosting the race around the Isle of Wight in 1851 won by the schooner America , which took home what became known as the America’s Cup. The Squadron donated the Cup itself in 1851 and mounted a number of challenges to win it back.

More than 160 years later the America’s Cup has still never been won by a British challenger, but now the commodore believes the Royal Yacht Squadron has “the best chance we have ever had” with its sponsorship of Ben Ainslie Racing as official British challenger for the 2017 Cup.

- 1. Flying the white ensign

- 2. Bicentenary celebrations

- 3. Inside the Castle

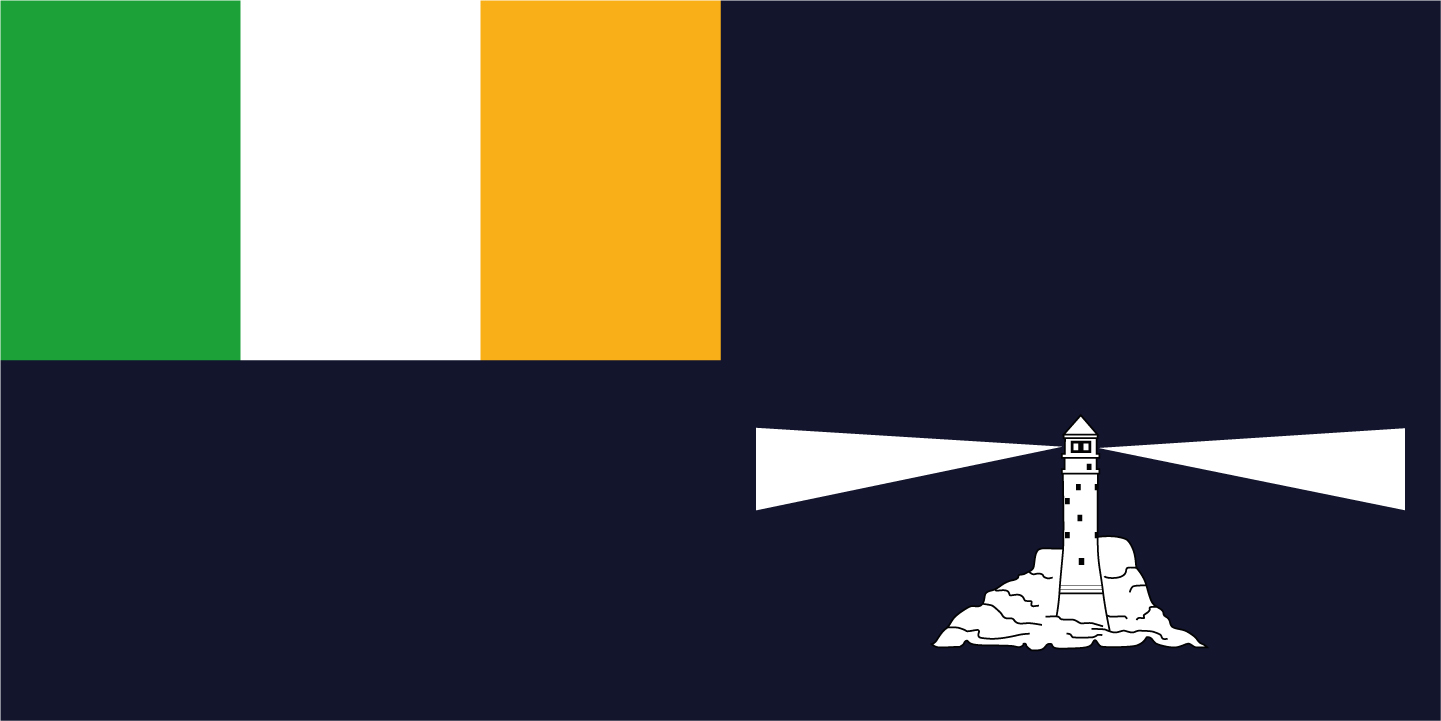

Flag of Royal Yacht Squadron

image by Clay Moss , 27 May 2007

Lloyd's Register of Shipping, London [UK], 1961(?) shows the Royal Yacht Squadron (United Kingdom). Since this publication is from later times, it shows a St. George white ensign. And it shows the same burgee as on above, except for one detail: The crown is different. Comparing with gb-crown.html , I'd say the crown looks like a Tudor Crown. I would even go so far as to say that that would make sense, for a burgee of a club of that age. But I'm not an expert on the matter, so I have to ask whether it would still make sense to use that crown 1961-ish. And then of course, comes the question of the change to the current style. Peter Hans van den Muijzenberg , 2 October 2014

A circa 1910 version of this burgee at https://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/212316.html uses a Tudor crown. Peter Hans van den Muijzenberg , 3 May 2019

First flags of Royal Yacht Squadron

image by Peter Hans van den Muijzenberg and Antonio Martins , 2 October 2014

image by Martin Grieve , 10 July 2007

Perrin (p.137) reports that the club's first flag (unofficially adopted) was a plain White Ensign without a Cross of St George in the fly, however, following official objections this was withdrawn and the club flew an undefaced Red Ensign between 1821 and 1829. In 1829 a permission to fly the "St George's or White Ensign" was granted, which the club still flies. Christopher Southworth , 25 December 2005

The origins of the wearing of the White Ensign by the Royal Yacht Squadron

Published by icc on may 3, 2023 may 3, 2023.

Extracted from ’Memorials of the Royal Yacht Squadron’ by Montague Guest (Librarian of the RYS) and William B Boulton, printed in London in 1902.

In 1859 was agitated the famous grievance of the supposed privileged possessed by the [Royal Yacht] Squadron of flying the White Ensign. A debate in Parliament and the publication of a Blue Book were necessary to compose the agitation of the group of the aggrieved ones in this matter. It was really, in essence, a very simple one, which had been somewhat complicated by the blundering of a clerk at the Admiralty, and the privilege as a fact was no privilege at all. As some misconception of the matter still exists, it may perhaps be well but it’s history should here be plainly stated.

….the vessels of the Squadron were by successive concessions of foreign governments granted privileges of exemption from port dues in foreign harbours, which placed them as pleasure vessels in a class apart from merchant vessels. [Briefly, this was because Squadron yachts, many of them armed and often with royalty or the ‘great and good’ on board, frequently visited foreign ports together with the British fleet. It was for this reason also that King William IV decreed in 1833 that the ‘Club’ should be called the ‘Squadron’.] These privileges in fact set them on the same footing as the King’s ships and it was felt by the Admiralty that a distinguishing ensign for these vessels was necessary for the convenience of the officials of the foreign Governments whose harbours they visited. There were only three ensigns available for the purpose – the Red, the White, and Blue. Of these the Red was already allocated to merchantmen, the White was worn then, as now, by the King’s ships, and the Blue by another class of vessel under the Admiralty – transports and the like. The privileges granted by foreign Governments to yachts being exactly those enjoyed by the King’s ships, it no doubt occurred to the Admiralty that the same ensign would be most suitable as a distinguishing flag for the pleasure vessels. In any case, as we have seen, permission to wear the White or St George’s Ensign was given to the Squadron by a warrant of the Admiralty in the year 1829.

It is important to note that the wearing of the ensign was not confined to the yachts of the Squadron but was permitted by those of any other recognised yacht clubs who chose to apply for it. Most of the clubs existing at the time availed themselves of the permission – the Royal Thames, the Royal Eastern, and the Royal Western Yacht Clubs, among others. Shortly after 1829 the Irish members of the Royal Western Yacht Club seceded and formed a club of their own entitled the Royal Western of Ireland Yacht Club. This club was granted the use of the White Ensign in 1832 in circumstances which show how little the flag was valued at the time, and that its use was not regarded in any way as a privilege. Mr O’Connell, the original Commodore of that club, addressed a letter to the Admiralty dated the 30th January, 1832 which contain the following passage:- “A White Ensign has been granted to the Royal Yacht Club, a Red Ensign to the Royal Cork, a Blue Ensign to the Royal Northern, and as the only unoccupied national flag, we have assumed the Green Ensign.”

To this the Secretary of the Admiralty replied:- “I am commanded by my Lords Commissioners to acquaint you that you may have as a flag for this club either a Red, White or Blue Ensign with such device thereon as you may point out, but their lordships cannot sanction the introduction of a new colour to be worn by British ships.”

The Irish club then chose the White Ensign, not considering it as any privilege, as is evident from Mr. O’Connell’s letter, but rather the reverse, and they added a crown, and a very small wreath of pale shamrock leaves as a distinguishing mark. So, the matter rested for ten years.

Meanwhile as the number of yacht clubs and of private vessels increased there were constant complaints reaching the Admiralty through the Foreign Office of irregularities committed in foreign ports by owners of pleasure vessels flying the White Ensign. There were charges of smuggling, of evasions of quarantine regulations, of landing and embarking passengers, and of a general abuse of the privileges which the flag conferred in foreign ports – privileges which had been granted to yachtsman entirely by the efforts of the Royal Yacht Squadron in the early days. There was a continual correspondence between the Admiralty and the secretary of the Squadron on the subject during those ten years which is preserved at the Castle [clubhouse of the RYS in Cowes on the Isle of Wight], and goes to show that a great part of that gentleman’s time was spent explaining that such and such a vessel which had committed such and such an outrage at Lisbon or Marseilles or Naples had no connection with the club. These irregularities had the natural result of bringing odium upon other yachtsmen flying the same ensign and who were innocent of any abuse of its privilege, and the nuisance at last became so injurious to the reputation of the Squadron that a meeting of the club in 1842 passed the following resolution:- “The meeting requested the Earl of Yarborough to solicit the Admiralty to alter the present colours of the Royal Yacht Squadron, or permission to wear the Blue Ensign, etc, in addition, in consequence of so many yacht clubs and private yachts wearing colours similar to those at present worn by the Royal Yacht Squadron.”

There followed a correspondence between Lord Yarborough and the Admiralty in which the former made complete of, “the many irregularities committed by persons falsely representing themselves as members and bringing undeserved disgrace on the Royal Yacht Squadron.” The result of the correspondence appears in a letter from Mr. Sidney Herbert to the Secretary of the Squadron dated from the Admiralty on July 22nd, 1842. The Admiralty refused permission to the Squadron to change their flag and decided to confine the use of the White Ensign to its members. “ I am commanded by my Lords,” wrote Mr. Herbert, “to inform you that they have consented to much of the above request as relates to the privilege of wearing the White Ensign being confined to the Royal Yacht Squadron, and that they have taken measures that the other yacht clubs may wear such other ensigns only as shall be easily distinguished from that of the Royal Yacht Squadron.” In pursuance of this decision all clubs were notified that the permission to fly the White Ensign was henceforward confined to the members of the Squadron and the matter again appear to be settled.

In notifying these clubs, however, the clerk at the Admiralty being unaware of the secession of the Royal Western of Ireland Yacht Club from that of England, addressed his letter to the English club only, and in the absence of any instructions to the contrary, the Irish club continued to fly the White Ensign. Matters rested there until a further correspondence between the Admiralty and yacht clubs arose in 1858. Some years previously the Admiralty had issued particular warrants to the owners of particular vessels in addition to the general warrant issued to the clubs as corporate bodies. In that year the Royal Western of Ireland Yacht Club applied for particular warrants for its members, but was a first refused on the ground, ”that it was defying the Admiralty by flying the ensign, and that the accidental omission of a letter in1842 was not considered to confer a claim to exemption from the general rule then established, viz. the restriction of the privilege of wearing the White Ensign to the Royal Yacht Squadron.” On renewed application, however, the Admiralty weakly gave way and issued particular warrants to members of the Royal Western of Ireland Yacht Club. This was immediately seized upon by another Irish club, the Royal St George’s, as a grievance. Its Commodore, the Marquess of Conyngham, wrote to the Admiralty to the effect that his club, “felt aggrieved that a club in no way better conducted – the Royal Western of Ireland Yacht Club – should be permitted to carry the White Ensign, as it appears that this privilege is no longer confined to the Royal Yacht Squadron,” and requested permission for the club to again fly the flag. The matter was at length set at rest by the Admiralty in a letter to Lord Wilton as Commodore of the RYS.

Admiralty 25th June 1858 “My Lord, – I am commanded by my Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty to acquaint your lordship that my Lords, having received some recent application from yacht clubs for permission to wear the White Ensign of Her Majesty’s fleet, have considered that they may have to choose between the alternative of reverting to the principal established in the year 1842 whereby the privilege was restricted to the Royal Yacht Squadron, or to extend still further the concession which was made in this respect to the Royal Western Yacht Club of Ireland in the year 1853, and that they have decided on the former alternative. They have accordingly cancelled the warrants authorising the vessels of the Royal Western Yacht Club of Ireland to wear the White Ensign, and this privilege for the future is to be enjoyed by the Royal Yacht Squadron only. I am, my Lord, your most obedient servant H Corry”

Such is the history of the White Ensign in relation to pleasure vessels. The matter was twice before Parliament, once in 1858 when an Irish member found a grievance in the decision of the Admiralty, and in later times in 1883, when Lord (then Mr.) Brassey, replying to Mr. Labouchere for Sir Henry Campbell Bannerman, cited the minute of 1842, and declared that, “as the matter was historical, he was not authorised to make any changes.” Whatever privilege is attached to the wearing of the flag was never sought by the Squadron, and it was not valued by other clubs until the irregularities of many private owners resulted in its use being confined to the old club which had first flown the flag. As a writer of 1858 pointed out, its wearing by the vessels of the Squadron alone eventually gave it a distinction among yacht ensigns, and there would probably have been the same struggle for its possession had the Squadron flown an ensign of purple or pink.

(Transcribed from the original text by John Clementson, May 2019)

Related Posts

Cormorants and shags: fish-eating sentinels!

by Bob Brown Bird Island, Strangford Lough. Seen close at hand, cormorants’ ‘scaly’ patterned plumage is quite attractive. We’ve all seen them: dark, brooding birds, perched on rocks, shipwrecks, harbour pilings, navigational beacons, and small Read more…

“Stupid Me”

By Alex Blackwell You know you are stupid, at least I think I am, when something ‘hits you in the eye, like a big pizza pie’. It is like when you are sailing along at Read more…

Ireland’s centenaries ashore are matched by sailing centenaries afloat

By WM Nixon (From Afloat Ireland) In Ireland, we’re living through the Decade of Centenaries in terms of marking conflict-laden historical events and major national happenings ashore. So it says everything about the blissful sense Read more…

Ask the publishers to restore access to 500,000+ books.

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

The Royal Yacht Squadron; memorials of its members, with an enquiry into the history of yachting and its development in the Solent; and a complete list of members with their yachts from the foundation of the club to the present time from the official records. By Montague Guest and William B. Boulton

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

12,208 Views

3 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

For users with print-disabilities

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by liz ridolfo on June 28, 2007

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

BRITANNIA RULES THE WAVES AND AMERICA WAIVES THE RULES

The Lipton era of competing for the America’s Cup drew to a close upon his passing on the 2nd October 1931 after a summer of speculation that a sixth challenge would be forthcoming under the flag of the Royal Yacht Squadron to which he had finally been elected a member, earlier in the year.

With the Great Depression biting across the globe, thoughts of building large, technically advanced yachts for the upper-class pursuit of yachting were not high in the minds of owners on both sides of the Atlantic. As austere times ensued, the call for smaller racing yachts was being heard by the New York Yacht Club who initiated an international competition for the growing 12-Metre class that it was thought could well all but kill off the J-Class with its huge demands on money and resources – particularly in light of the recent money-no-object campaigns of the likes of Vanderbilt and Lipton.

But over in England, a significant passing of the patriarchal baton was well underway with the emergence on the yachting scene of Thomas Octave Murdoch Sopwith, an aviation entrepreneur who had been bankrupted by punitive anti-profiteering taxes post the First World War but had re-entered the business as Chairman of Hawker Aviation in 1920 and went on to create some of the most iconic and commercially successful planes in the world.

Sopwith’s eye for innovation and a determination to apply the learnings of his aviation business into the science of America’s Cup race boats led to a swift purchase of Shamrock V from the estate of Sir Thomas Lipton and the retention of Charles Nicholson as principal designer for a new J-Class commission. Furthermore, Sopwith secured the talents of Frank J. Murdoch, one of England’s finest engineers who was subsequently described as a “genius and a gentleman” in the Herreshoff Marine Museum archives, to raise the technological approach of what would become England’s finest challenger for the America’s Cup.

The commissioning and build process for the Endeavour programme begin in earnest at the Camper & Nicholson boatyard in Gosport in 1933 when the formal challenge was issued by the Royal Yacht Squadron in Cowes on behalf of Thomas Sopwith (he wasn’t Knighted until much later in 1953) to the New York Yacht Club. Harold Vanderbilt, aware of moves afoot in England, in particular the follow-on design from Shamrock V from the design board of Charles Nicholson in the yacht ‘Velsheda,’ had already commissioned Starling Burgess to work up plans should the inevitable challenge arrive.

When it did, the Americans were at full tilt after a lengthy tank-testing programme at Ann Arbor in Michigan that produced the lines for Rainbow – a full two feet longer on the waterline and six feet longer overall than the prior defender, Enterprise. New class rules had come into effect in the J-Class which eliminated below-deck winches and demanded certain standards of accommodation but alongside the commissioning of the new Rainbow, the Morgan family’s yacht Weetamoe and the heavily modified Yankee, that was shortened and slimmed around the mid-point in a remarkable Herreshoff transformation quite unheard of at the time, were to contest the slot for the defence of the America’s Cup and secure the nomination of the New York Yacht Club.

Of note and relevance for that summer of trials was the inclusion of women in significant roles on both the Yankee and indeed the Endeavour. Elizabeth ‘Sis’ Hovey, daughter of Chandler Hover, the manager of Yankee, was appointed as an active member of the afterguard throughout the trials, whilst Mrs Phyllis Brodie Sopwith, Thomas’s second wife whom he married in 1932 after the death of his first wife Beatrice in 1930, assumed the significant role as official timekeeper in the afterguard of Endeavour throughout the summer of 1934. It was certainly not the first time that women had been involved in Cup racing, with Mrs Susan Henn, wife of skipper Lieutenant William Henn, sailing aboard the Galatea to its defeat in 1886 and Lord Dunraven’s daughter, the Honourable Enid Wyndham-Quinn sailing aboard the Valkyrie II in the 1893 Cup defeat.

Rainbow was launched at the Herreshoff Yard in Bristol, Rhode Island a month after Endeavour in May 1934. The English yacht had slipped into the water at Gosport after the customary bottle of champagne was cracked by Phyllis Sopwith over her bows on April 16th, 1934, and was immediately commissioned, with a professional crew, on trial runs in the Solent. Endeavour was a feat of engineering that fused the nautical with the aeronautical sporting wind speed and direction instruments in the cockpit, an aerofoil shaped Duralumin mast, rod rigging (fitted later) and a novel bendy boom that had been nicknamed the ‘North Circular’ after the crescent road that runs across the top of London. It was an inauspicious start though with the boom snapping on a light air test-sail in the Solent, but Nicholson was quick to replace the boom with higher tensile stringers and the boat was sent to Harwich on the East Coast to face down the fastest boats of the British fleet.

Over in America however, things weren’t going smoothly. A change in the J-Class rules had gone against the Rainbow and Weetamoe in that their centreboards were found to be some 1200 pounds more than was permitted causing some dramatic, and rather panicked, last-minute alterations. Meanwhile Yankee, whose designer Frank C. Paine, has conformed to the new rules in the extensive refit at Herreshoff’s yard was more than ready to start the defender trials that spring. Both Rainbow and Weetamoe made the appointed day of the trials, but the Morgan family yacht was quickly eliminated in a quick-fire round of match-races, apparently being no match for either Yankee or Rainbow with the latter suffering its own dose of the slows in the early matchups. But Vanderbilt had form in working-up boats over the course of a season and with a crew comprised of many that had sailed with him on Enterprise, they had experience combined with a bottomless budget and the ensuing races against Yankee were thrillers.

If a campaign mistake could be attributed in hindsight to the Royal Yacht Squadron challenge of 1934, the unveiling of a quadrilateral working headsail in early trials in Weymouth Bay, was one that was deeply-rooted in the character of Thomas Sopwith. The genesis of this innovative piece of sailmaking that featured a double clew on the luff, thus creating in effect four sides to the sail, is still in doubt to this day but it was John Nicholson, the son of designer Charles Nicholson, that is widely credited with the Endeavour design that was built at Ratsey’s in Cowes. Upon receipt of the sail and whilst engaged in a tight race with Velsheda out in Weymouth Bay, Sopwith couldn’t resist the call for the sail much to the chagrin of Charles Nicholson who had firmly suggested that the sail should be trialled far out to sea in the English Channel to avoid prying eyes. In a matter of days, the design was in Newport, and it was a short time before both Rainbow and Yankee sported the sails that produced so much extra power that enhanced turning blocks were required to be retrofitted to the yachts. So sensational were the quadrilateral working-jibs that both Yankee and Rainbow sported them in a desperately close five-trial series in the summer of 1934. Vanderbilt’s well-drilled team once again extracted the maximum from their vessel, improving with each race after a loss in the opening flight by over six minutes.

Yankee was a well optimised J-Class for the lighter airs, so Vanderbilt ultimately got competitive in the pre-starts knowing that his crew were the better drilled and sailed in a way to try and force errors. In the afterguard of Rainbow, Vanderbilt eventually found the combinations that worked. Tensions were high at times between Starling Burgess and Vanderbilt who fell out briefly with the skipper bringing in Zenas Bliss as navigator at the behest of sail-manager Sherman Hoyt whilst Jack Parkinson replaced Bubbles Havemeyer as the secondary helmsman downwind. Burgess and Vanderbilt made-up and the former remained in change of rigging through the match – Bliss however remained as navigator and was to prove something of a master. Despite the trial racing being tight and hotly contested, the tale of the series saw Rainbow win four of the five races – the last by just one second – and the New York Yacht Club appointed Vanderbilt’s team to the task of defending the America’s Cup.

Over in England, Endeavour was putting all-comers to the sword in a series of races in Harwich and a further final trial series in and around the Solent and out further west to Torbay. Velsheda was the closest competitor, winning some notable battles in a variety of conditions, but ultimately Captain Fred Mountfield, skipper of Velsheda, came up short and Endeavour, with a record of eight wins from 12 races, was confirmed as the Challenger for the Royal Yacht Squadron.

However, things were about to turn for the worse at the conclusion of the trials on the 14th July 1934 when the professional crew of Endeavour presented Sopwith an ultimatum that they would not undertake the Atlantic crossing nor the Cup series in September 1934 unless they were paid substantially more money. The employment system at the time meant that sailors were only paid until the end of the summer sailing season after which the crew would return to their hometowns to seek work on fishing boats for the winter months. With the Cup so late, they would miss the opportunity to secure slots on the fishing boats and therefore sought compensation for their loss of earnings. This garnered little sympathy with Sopwith and in return he outlined an improved offer that fell short and resulted in 15 crew hands leaving the ship, all bar two, although all of the ‘officers’ accepted the conditions. In their place, Sopwith recruited willing amateurs from the Royal Corinthian Yacht Club on the East Coast.

With a new crew in place, Endeavour left Gosport on 23rd July 1934 escorted for the trans-Atlantic run by Sopwith’s motor-yacht Vita. Crowds lined the shoreline as it was felt that such a technical marvel had every chance, finally, of wresting the America’s Cup from the clutches of the Americans. On arrival in Bristol, Rhode Island, her huge metal, aerofoil in shape, mast was stepped at the Herreshoff yard and for the first time, the rod rigging that had been developed by Frank Murdoch at the Hawker Aircraft facility, were applied to the rig. When the two boats were lined up for inspection however, a row emerged over the interpretation of the J-Class rules regarding fixtures and fittings below deck. Rainbow was largely a stripped-out racer whilst Endeavour still featured extensive detailing and even a bath in the state-cabin for Thomas Sopwith. The English insisted on being allowed to remove the luxuries and after much debate in yachting circles, the request was finally acceded. One other contentious issue was Rainbow’s below deck winch, outlawed in the new rules, that was operated by a coffee-grinder above. Vanderbilt argued, successfully, that due to it being operated on deck it didn’t contravene the rule and the races for the America’s Cup began on 15th September regardless.

With President Franklin D. Roosevelt watching, the opening race of the 1934 America’s Cup was a thriller. A tight first leg to windward saw Rainbow round the top mark some 18 seconds up on the Challenger but a crucial error was called by the Americans who elected to launch a small parachute spinnaker whilst Endeavour set a much larger kite replete with a vertical line of holes down the centreline that aided air circulation and maintained stability. With the wind up at 15 knots, it was a big call from the English but within three miles they seized the lead and relentlessly pulled ahead. Vanderbilt took Rainbow on a circuitous course, trying desperately not to run before the wind but as the two boats came back on course deep into the run to the finish, it was Sopwith that was able to gybe for the line on a shorter course and recorded a two minute and nine second victory.

With the score at 1-0, the Americans grew worried by the threat that the English were posing, particularly in the stronger breeze and race two saw no respite with a solid 14 knots recorded at the America’s Cup buoy, the starting mark some nine miles SSE of the Brenton Reef Lightship. An uncharacteristic poor start predicated in the final approach to the line saw Vanderbilt down-speed at the starting gun despite holding the windward berth. Sopwith capitalised, driving Endeavour hard and powered through the lee of Rainbow on a fast-reaching leg to the first mark despite suffering a torn clew on the genoa in the pre-start manoeuvres when the hanks fouled on the inner forestay.

A mile from the outer mark, with the wind shifting forward, Sopwith called for the quadrilateral jib to be broken out and an additional large staysail to be set whilst the genoa was removed and in the ensuing upwind leg, the English matched the Americans tack for tack, all the while pulling ahead. Endeavour was 16 seconds up at the first mark but 1 minute 31 seconds up at the second with just a reach to the finish. However, without the powerful genoa, Endeavour set a ballooner on too shy a course and saw her lead dwindle as the Americans came fast astern. By the finish, Sopwith held on, and the final winning margin was some 51 seconds. 2-0 to the Challenger and it was game on for the America’s Cup.

After a cancelled day with no wind, the next race was held on the 20th September 1934 and it was a race where all seemed lost for the Americans until a remarkable piece of navigating turned the tide on the whole Cup contest. On a leeward / windward start, both boats set away under full canvas in a light and shifting north-easterly and quickly the more-canvassed Endeavour ground into a commanding lead. Some careless sail calls and debatable tactics from Vanderbilt saw Rainbow slip further and further behind, eventually reaching the outer mark some 6 minutes and 39 seconds behind with only a long reach on starboard to the finish. Handing the wheel over to Sherman Hoyt, Vanderbilt had all but given up and retired below for coffee and sandwiches, but Newport was about to serve up a classic.

Keeping close eyes on the boat ahead, Hoyt noticed the English falling into a hole in the wind and headed high to sail around. The wind was now well forward and both boats were headed close hauled. Sopwith threw in two tacks to try and stay to windward of Rainbow and in doing so, paid away her lead as the American boat straight-lined and the final of those tacks saw Endeavour wallow badly, unable to get up to speed. Rainbow sailed through to leeward and gained the lead whilst the navigators on both boats desperately tried to ascertain the position of the finishing buoy. Zenas Bliss on Rainbow called it to leeward and with that, a returning Vanderbilt gave the order to “carry on” with Endeavour up to windward and far off the lay-line to the mark. At the finish, Bliss had called it correctly and in a most dramatic and unexpected fashion, secured a 3 minute and 26 second victory.

2-1 but the pendulum had swung.

Now came a masterstroke from Vanderbilt, the undisputed genius at building his boats into winners. Recognising that Rainbow was at a considerable disadvantage downwind when dead-running under parachute spinnaker, he remembered that Yankee had enjoyed a similar advantage in the trials and immediately contacted Frank Paine, the designer of the yacht and who had sailed onboard during the trials, to join the Rainbow afterguard. Paine arrived and with him came one of the Yankee spinnakers whilst during the lay-day, Vanderbilt instructed for some 4,000lbs of ballast to be added in a search for better waterline performance.

And it was fireworks in the starting box for race four with Vanderbilt now determined to capitalise on his momentum, but it was a race where sharp practices, according to an English standpoint, were to be displayed and led to considerable dismay with the New York Yacht Club’s protest committee. An incident before the start as Endeavour gybed from a starboard reach to head back to the line with Rainbow not keeping clear and forcing the English to take avoiding action was the first debatable point but the protest wasn’t heard due to the absence of a protest flag. The second however, on the first reaching leg where Endeavour came up for a luff, is one that is still debated to this day. Having rounded the top mark ahead, the Challenger was caught short with less sail area up on the reach carrying her quadrilateral sail whilst the Defender had opted to change for a large genoa late on the beat into the top mark.

With more horsepower, Rainbow held high and started to close the gap whilst Endeavour had borne away below the rhumb-line in order to change up her sails. Once complete, Endeavour narrowed the gauge and went into a luff to defend her position which the Americans failed to respond to with Vanderbilt believing that the English angle meant she could not touch forward of the rigging. Sopwith bore away to avoid an inevitable collision but again, the protest flag wasn’t flown as the custom under the Yacht Racing Association rules in England was to fly the flag at the end of the race. The NYYC reverted to its own rules on the matter and held firm, insisting that a flag must be flown immediately in order to give the protested yacht the chance to counter-protest should they see fit. Rainbow seized the lead and sailed on to a bitter-sweet 1 minute 15 seconds victory and draw the series level.

Stepping ashore, Sopwith, having seen the improved performance of Rainbow on the reaching leg, reversed the decision to strip out the below-deck quarters taken when the two boats were measured and inspected before the series started, and ordered the 3,360lbs of weight to be replaced as ballast – whether Sopwith’s bath came back is not known!

Race five was held in 12 knots of building breeze on Monday 24th September 1934 and featured a leeward / windward course. Rainbow was first to set her parachute spinnaker under the control of Frank Paine and quickly established a lead whilst Endeavour struggled with crew work. Vanderbilt was looking imperious and even a slight chafing of the spinnaker that turned into a tear towards the bottom mark and a very near man overboard incident that was thankfully recovered through very quick thinking by the well-drilled crew, they drew out a lead of some 4 minutes 38 seconds before the turn and beat home. Rainbow camped on Endeavour’s wind and the result was never in doubt, recording a win by 4 minutes and 1 second to take the lead in the series.

With Sopwith smarting from the perceived injustices he felt from the incidents in race four and Vanderbilt determined to establish his dominance and close out the series, race six began yet again with an incident in the dying seconds of the pre-start. In the final approaches to the line again on a leeward / windward course, Endeavour was heading to the line reaching on port tack whilst Rainbow was borne away running for the portside of Endeavour on starboard gybe. At the last minute, Vanderbilt passed underneath the stern of Endeavour, tacked and broke out his large genoa. Both boats protested but ultimately both were withdrawn, with Sopwith the first to retract, but it was Endeavour that held the lead and crossed the start line with a 46 second advantage.

After half an hour, with both boats sailing under genoa, Rainbow drew level and Endeavour luffed her head to wind gaining a significant 100-yard advantage immediately afterwards as the boats came back on course, but the race was ultimately decided on Vanderbilt’s decision to launch a small spinnaker a little while later, whilst Endeavour continued under her genoa.

As the first mark approached, and with Rainbow’s forestay hidden from view as the trailing yacht, Vanderbilt called for her quadrilateral jib to be hoisted as he recognised that the wind had built too much for a larger genoa on the returning windward leg. Sopwith’s crew had failed to see the move and rounded 1 minute and 9 seconds up but with too much sail area in the genoa to control. Immediately Vanderbilt initiated a tacking duel that the Challenger was simply no match for and with her quadrilateral working perfectly and under the expert trim of the Rainbow crew and a fortunate 25-degree shift in her favour, by the final top mark, the American’s lead was almost three minutes.

But the final race of 1934 was anything but done. Rainbow rounded and were forced to launch a parachute spinnaker borrowed from the Morgan family’s Weetamoe that was full in the foot and refused to set properly. Endeavour meanwhile launched her enormous race spinnaker and closed the gap, bring up fresh breeze coming out of Buzzards Bay. Vanderbilt asked for Sherman Hoyt to replace Jack Parkinson on the wheel for the tense run to the finish and the Hoyt / Bliss magic was once again re-enacted. Hoyt asked Bliss for the bearing to the finish mark but also a point one mile to leeward of the finish, gambling on Sopwith’s tendency to try and keep a cover regardless of course. True to form, Sopwith was forced to sail lower and slower, and almost by the lee, to try and cover Rainbow who were steering a false course knowing that if Endeavour got to her lee quarter, they could harden up and steer directly for the finish line. The tactic worked a treat by two master tacticians and with just a mile left to run, they sheeted on and held course to record a stunning 55 second victory against the odds and retain the America’s Cup for the New York Yacht Club.

Sopwith had genuinely come closer than any challenger before but ultimately was outclassed on the water by a team operating at the very maximum of what their boat was capable of. In Harold Vanderbilt, they met a fierce competitor whose working-up of boats was now legendary but in Sherman Hoyt and Zenas Bliss, the Endeavour afterguard simply had no answer to their navigational and tactical genius. Speaking afterwards, Sopwith, still unhappy with how the series had unfolded, commented: “I do not feel vindictive at my treatment at the hands of the New York Yacht Club, but I do feel completely disillusioned. I came over here for the good of the sport but found that the races were run as a big business, something I was not prepared to contend with.”

The aftermath of the 1934 regatta was mired in accusation and counter-claims played out in communications between the yacht clubs and in the media by Sopwith, Charles Nicholson and Vanderbilt with questions around sailing rules interpretations high on the agenda. The Americans stuck to their lines, the English contested furiously and the famous headline recorded on both sides of the Atlantic after the infamous race four became part of America’s Cup legend: “Britannia rules the waves but America waives the rules.”

Thomas Sopwith would be back – more the wiser for the experience.

The Royal Yacht Squadron

Frequent reference to the Royal Yacht Squadron will be found elsewhere in this work, and under this particular heading no attempt can be made to give anything further than the merest outline of this club’s history.

The Squadron dates from 1815. For some few years prior to that date the pastime of sailing had been growing in favour in the Solent, and a number of visitors were attracted to Cowes every summer to indulge in the sport. It was only natural that these first yachtsmen should ultimately form a club to carry on their sport in an organized fashion, and so we find that a meeting was held at the Thatched House Tavern in St. James’s Street on June 1, 1815, under the presidency of Lord Grantham, when it was decided to form the Yacht Club, which was to consist of men interested in the sailing of yachts in salt water.

The qualification for membership was the ownership of a vessel not under 10 tons, and the original subscription was two guineas, with an entrance fee, afterwards imposed, of three guineas.

In 1817 the Prince Regent became member of the organization, and he was the first of the long list of Royal patrons which have honoured the club. Upon the Prince Regent becoming King in 1820, he consented to give a royal title to the club, and from that date it was known as the Royal Yacht Club – the first yacht club to enjoy that distinction. For some years after the formation of the club but little was done in the way of organized racing; but in the year 1826 a regatta was held, on August 10, at which a gold cup of the value of £100 was competed for. The winner of this, the first cup ever competed for under the auspices of the Royal Yacht Club, was Mr. Joseph Weld’s famous cutter, Arrow.

In the following year, in addition to cups presented by the club and by the town of Cowes, the regatta was made memorable by the presentation of a cup by King George IV. This was the first royal trophy presented for competition in a yacht race, and was won by Mr. Maxse’s cutter Miranda.

The club continued to be known as the Royal Yacht Club until the year 1833, when, in July of that year, King William IV, as a mark of approval of an ‘institution of such national utility,’ authorized the name to be altered to that of the Royal Yacht Squadron, the name by which it has ever since been known. His Majesty followed the example set by King George IV, and gave a cup to be competed for every year, and this custom has been observed by the reigning monarch ever since.

Up to the year 1829 there had been several alterations in the flag flown by yachts belonging to the club, but in that year the Admiralty issued a warrant authorizing members to fly the white ensign, and at the same time the white burgee, as we know it to-day, was adopted.

The application of steam power to yachts was viewed with much disfavour in the Squadron in earlier days, and at a meeting held at the Thatched House Tavern in 1827 the following resolution was passed : ‘Resolved that as a material object of this club is to promote seamanship and the improvements of sailing vessels, to which the application of steam-engines is inimical, no vessel propelled by steam shall be admitted into the club, and any member applying a steam-engine to his yacht shall be disqualified thereby and cease to be a member.’ In 1844 this rule was somewhat modified by admitting steam yachts to the club of not less than 100 horse-power, and in 1853 all restrictions in regard to steam were removed.

The present quarters, the Castle, were taken possession of in 1858.

The first Commodore was the Earl of Yarborough, who held the post from 1825 to 1846. He was succeeded by the Marquis of Donegall, who occupied the position for two years, and was in turn succeeded by the Earl of Wilton, who retained the post from 1849 to 1881. In 1882 the office was filled by H.R.H. the Prince of Wales, and retained by him until 1901, when, upon becoming King, His Majesty became Admiral, and the Marquis of Ormonde was elected to the Commodoreship.

The Vice-Commodores during the same period have been : The Earl of Belfast, from 1827 to 1844, and afterwards (as the Marquis of Donegall) from 1845 to 1846; Sir Bellingham Graham, Bart., from 1847 to I850 ; C. R. M. Talbot, Esq., M.P., from 1851 to 1861; the Marquis of Conyngham, from 1862 to 1875; the Marquis of Londonderry, from 1876 to 1884 ; the Marquis of Ormonde, from 1885 to 1901 ; the Duke of Leeds, 1901 to present day.

The Royal Yacht Squadron has often been referred to as the most exclusive club in the world. Its list of Royal members, past and present, is an imposing one, and includes : H.M. King George IV; H.M. King William IV; H.R.H. the Duke of Gloucester; H.M. Queen Victoria; H.R.H. Prince Albert (Prince Consort); H.I.M. Nicholas, Emperor of Russia; H.R.H. Prince Louis de Bourbon; H.I.H. the Grand Duke Constantine; H.M. William III, King of the Netherlands; H.M. Napoleon III; H.M. King Edward VII; H.R.H. the Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha; H.R.H. the Duke of Connaught; H.R.H. Prince Henri de Bourbon; H.M. Oscar I, King of Norway; H.I.M. William II, German Emperor; H.R.H. Prince Henry of Prussia; H.R.H. Prince Henry of Battenberg; H.R.H. the Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin; Prince Ibrahim Halim Pacha; H.M. the King of the Belgians; H.R.H. the Duke of Abruzzi; H.R.H. the Prince of Wales; H.M. Alfonso XIII., King of Spain.

RYS Flag Officers 1825-Present

The Yacht Club was founded in 1815 for Members to meet twice a year to dine and share their mutual interest in yachting. It had no premises so had no real need of officers; various Members chaired the bi-annual meetings in the early years before there was a Commodore, viz: Lord Grantham, Brydges Pope Blachford Esq, the Earl of Craven, Hon Charles Anderson Pelham Esq (later as Lord Yarborough), the Marquis of Anglesey, William Baring Esq, Captain The Hon.B Pellew, the Duke of Norfolk, Sir George Leeds and the Earl of Darnley.

Until 1825 the Club held its annual Cowes meetings at several local hostelries. The Medina Hotel at East Cowes, home of the annual regatta ball, was most favoured; it was also near the Customs House where the Club’s first Secretary was a Customs Officer. In 1824 it was decided to investigate providing a coffee room for the Club and a committee was set up comprising Lord Yarborough, The Hon W Hare, Sir George Thomas, James Weld Esq and Henry Perkins Esq. The result was the Club’s first premises ‘Parade House’, leased from Mrs Sarah Goodwin in 1825. This building was on The Parade across the road from the Castle; it later became the Gloster Hotel and has since been replaced by the Gloster Apartments. Once the Club had premises trustees and a committee were required, once it started its yacht racing programme in 1826 stewards (forerunner of the Yachting Committee) were necessary also.

Commodore and Vice Commodore

The first mention of a Commodore is in the Club Minutes of 18th June 1822. A tradition of parading the yachts as part of the Regatta had begun in 1814 but the 1822 Minutes record that on the 1st and 3rd Mondays of each month [i.e. through the summer], Club yachts would assemble in Cowes Roads for the purpose of sailing together under the directions of a Commodore to be appointed for the day. A further Minute, a month later, suggests this had not worked quite as planned, stating ‘the original proposition of assembling the vessels … [had been] … made with a far different view from that of racing and shewing superiority of sailing’. It went on to give more detailed instructions for squadron sailing to ‘tend to the comfort of all, and particularly of the ladies who may honor the meeting with their presence’.

The Marquis of Anglesey and Stephen Challen Esq were the first Commodores for the day in 1822. In 1823 it was the Hon Charles Anderson Pelham who led the Club yachts to Plymouth, taking the salute as Commodore; in 1824 he led them again to the West Country and across to Cherbourg. In 1825 he had no yacht but is still referred to as Commodore in the local and yachting press. The Club Minutes have no record of such a permanent appointment but by 20th September 1826 they too are referring to him as ‘our Commodore’. His 351 ton Falcon, launched in 1826, became the Club’s flagship. In September 1827 Lord Belfast was appointed Vice Commodore.

Commodores originally served for life, the then Vice Commodore succeeding to the position when the Commodore left office. This practice continued until Sir Ralph Gore died in 1961. At that time HRH The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, was approached and agreed to become Commodore on condition that the appointment would henceforth be for a fixed term of six years. The term for Commodores and Vice Commodores was subsequently altered to five years and then to four, thus allowing today for a new Flag Officer to take office each year.

Rear Commodores

Prince Philip oversaw other reforms, doing much to transform the Club and bring it into the 20th century. Believing Cowes Week to be somewhat confusing for participants, one of his suggestions was the appointment of two Rear Commodores to give more attention to the administration of yachting generally, and this, together with his suggestion for the establishment of Cowes Combined Clubs, marked the rapid modernisation of the event. Serving overlapping four year terms, nowadays one Rear Commodore is responsible for yachting, the other for finance.

King William IV could be considered the first Admiral of the Royal Yacht Squadron: it was he who conferred that name on the Club in 1833, and he constituted himself its head. The idea was revived in 1901 on the death of Queen Victoria since the Prince of Wales could not continue to be Commodore once he became King Edward VII. The practice of the monarch being Admiral as well as Patron continued with subsequent monarchs until the succession of the present Queen when she became Patron and HRH The Prince Philip became Admiral.

1825-1846 - The Earl of Yarborough 1847-1848 - The Marquis of Donegal 1849-1881 - The Earl of Wilton 1882-1900 - HRH The Prince of Wales 1901-1919 - The Marquis of Ormonde 1920-1926 - The Duke of Leeds 1927-1942 - Sir Richard Williams-Bulkeley 1942-1943 - The Marquis Camden 1943-1947 - Sir Philip Hunloke 1947-1961 - Sir Ralph Gore 1962-1968 - HRH The Prince Philip Duke of Edinburgh 1968-1974 - The Viscount Runciman of Doxford 1974-1980 - Major General the Earl Cathcart 1980-1986 - Sir John Nicholson 1986-1991 - John Roome Esq 1991-1996 - Maldwin A C Drummond Esq 1996-2001 - Peter C Nicholson Esq 2001-2005 - The Lord Amherst 2005-2009 - The Lord Iliffe 2009-2013 - M.D.C.C. Campbell Esq 2013-2017 - The Hon. Christopher Sharples 2017-2021 - T J R Sheldon Esq 2021-Presnt - The Hon Sir James Holman

Vice Commodores

1827-1847 - The Earl of Belfast (to 1844), subsequently Marquis of Donegal 1848-1850 - Sir Bellingham Graham 1851-1861 - C R M Talbot Esq 1862-1875 - The Marquis Conyngham 1876-1884 - The Marquis of Londonderry 1885-1900 - The Marquis of Ormonde 1901-1919 - The Duke of Leeds 1920-1926 - Sir Richard Williams-Bulkeley 1927-1943 - The Marquis Camden 1945-1947 - Sir Ralph Gore 1948-1954 - The Viscount Camrose 1954-1965 - The Marquis Camden 1965-1971 - Sir Kenneth Preston 1971-1977 - The Earl of Malmesbury 1977-1983 - Major General Sir Robert Pigot Bt 1983-1988 - Sir Charles Tidbury 1988-1993 - A J Sheldon Esq 1993-1998 - The Lord Amherst of Hackney 1998-2003 - Michael D C Campbell Esq 2003-2007 - Sir Nigel Southward 2007-2011 - Ian Laing Esq 2011-2015 - C R Dick Esq 2015-2019 - Colin Campbell Esq 2019-2023 - Martin Stanley Esq 2023- Present - P L F French Esq

1962-1964 - Colonel The Earl Cathcart 1962-1966 - The Viscount Runciman of Doxford 1964-1968 - Lt Colonel A W Acland 1966-1970 - John D Russell Esq 1968-1972 - Stewart H Morris Esq 1970-1974 - Roger Leigh-Wood Esq 1972-1976 - Major P R Colville 1974-1978 - Brigadier Sir Richard Anstruther-Gough-Calthorpe 1976-1980 - J M F Crean Esq 1978-1982 - Sir Eric Drake 1980-1984 - J W Roome Esq 1982-1986 - Sir Maurice Laing 1984-1988 - Commander G H Mann RN 1986-1990 - J R D Green Esq 1988-1992 - D A Acland Esq 1990-1994 - P C Nicholson Esq 1992-1996 - A K S Franks 1994-1998 - A H Matusch Esq 1996-2000 - D F Biddle Esq 1998-2002 - Dr J H P Cuddigan 2000-2004 - R W C Colvill Esq 2002-2006 - John Grandy Esq 2004-2008 - John Godfrey Esq 2006-2010 - Captain S A V van der Byl RN 2008-2012 - John Raymond Esq 2010-2014 - David Aisher Esq 2012-2016 - The Hon Patrick Seely DL 2014-2018 - J P L Perry Esq 2016-2020 - C Russell Esq 2018-2022 - Robert M Bicket Esq 2020-Present - Jeremy Bennett Esq 2022-Present - B B Huber Esq

Royal Yacht Squadron

The Castle, Cowes, Isle of Wight, P031 7QT

Tel: +44 (0) 1983 292 191

Photography

National News | Today in History: August 22, first America’s…

Share this:.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

Today's e-Edition

- Latest News

- Environment

- Transportation

Breaking News

National news | fruit fly discovery puts part of alameda county into quarantine, national news, national news | today in history: august 22, first america’s cup trophy, also on this day, black panthers co-founder huey p. newton was shot to death in oakland, california.

Today in history:

On Aug. 22, 1851, the schooner America outraced more than a dozen British vessels off the English coast to win a trophy that came to be known as the America’s Cup.

Also on this date:

In 1791, the Haitian Revolution began as enslaved people of Saint-Domingue rose up against French colonizers.

In 1922, Irish revolutionary Michael Collins was shot to death, apparently by Irish Republican Army members opposed to the Anglo-Irish Treaty that Collins had co-signed.

In 1965, a fourteen-minute brawl ensued between the San Francisco Giants and the Los Angeles Dodgers after Giants pitcher Juan Marichal stuck Dodgers catcher John Roseboro in the head with a baseball bat. (Marichal and Roseboro would later reconcile and become lifelong friends.)

In 1968, Pope Paul VI arrived in Bogota, Colombia, for the start of the first papal visit to South America.

In 1972, John Wojtowicz (WAHT’-uh-witz) and Salvatore Naturile took seven employees hostage at a Chase Manhattan Bank branch in Brooklyn, New York, during a botched robbery; the siege, which ended with Wojtowicz’s arrest and Naturile’s killing by the FBI, inspired the 1975 movie “Dog Day Afternoon.”

In 1989, Black Panthers co-founder Huey P. Newton was shot to death in Oakland, California.

In 1992, on the second day of the Ruby Ridge siege in Idaho, an FBI sharpshooter killed Vicki Weaver, the wife of white separatist Randy Weaver .

In 1996, President Bill Clinton signed welfare legislation that ended guaranteed cash payments to the poor and demanded work from recipients.

In 2003, Alabama’s chief justice, Roy Moore, was suspended for his refusal to obey a federal court order to remove his Ten Commandments monument from the rotunda of his courthouse.

In 2007, A Black Hawk helicopter crashed in Iraq, killing all 14 U.S. soldiers aboard.

Today’s Birthdays:

- Author Annie Proulx (proo) is 89.

- Baseball Hall of Famer Carl Yastrzemski is 85.

- Pro Football Hall of Fame coach Bill Parcells is 83.

- Writer-producer David Chase is 79.

- CBS newsman Steve Kroft is 79.

- International Swimming Hall of Famer Diana Nyad is 75.

- Baseball Hall of Famer Paul Molitor is 68.

- Rock guitarist Vernon Reid is 66.

- Country singer Collin Raye is 64.

- Rock singer Roland Orzabal (Tears For Fears) is 63.

- Singer Tori Amos is 61.

- International Tennis Hall of Famer Mats Wilander (VEE’-luhn-dur) is 60.

- Rapper GZA (JIHZ’-ah)/The Genius is 58.

- Actor Ty Burrell is 57.

- Celebrity chef Giada De Laurentiis is 54.

- Actor Rick Yune is 53.

- Singer Howie Dorough (Backstreet Boys) is 51.

- Comedian-actor Kristen Wiig is 51.

- Talk show host James Corden is 46.

- Pop singer Dua Lipa is 29.

- Report an error

- Policies and Standards

More in National News

National News | Today in History: September 8, Ford pardons Nixon

National News | Suspect sought after five people shot, wounded in Kentucky

National News | Today in History: September 7, Germany launches Blitz on UK

National Politics | Kremlin disinformation tactic reveals new efforts to sway US elections

COMMENTS

The Royal Yacht Squadron (RYS) is a British yacht club with a history of naval and royal connections. It has a clubhouse on the Isle of Wight, a burgee with a crown and a St George's Cross, and a challenge for the America's Cup.

The Crossword Solver found 30 answers to "Royal Yacht Squadron flag (5,6)", 11 letters crossword clue. The Crossword Solver finds answers to classic crosswords and cryptic crossword puzzles. Enter the length or pattern for better results. Click the answer to find similar crossword clues. Enter a Crossword Clue.

Learn about the origins, achievements and traditions of the Royal Yacht Squadron, one of the most prestigious and exclusive yacht clubs in the world. Explore its timeline from 1815 to 2016, from its association with the Royal Navy to its involvement in international racing and cruising.

Learn about the most prestigious yacht club in Britain, founded in 1815 by King George IV and based in Cowes. Discover its members, trophies, traditions and challenges for the America's Cup.

In 1855, the Squadron leased the Castle from the Government and commissioned the architect Anthony Salvin to convert it from a coastal fortress to a clubhouse. On 6th July 1858 the Signalman's ledger recorded, 'Hoisted the flag of the R.Y.S. at the Castle'. During the Crimean War of 1853-6, Squadron yachts took supplies to British soldiers.

Royal Yacht Squadron. The Castle, Cowes, Isle of Wight, P031 7QT. Tel: +44 (0) 1983 292 191

First flags of Royal Yacht Squadron. image by Peter Hans van den Muijzenberg and Antonio Martins, 2 October 2014. image by Martin Grieve, 10 July 2007. Perrin (p.137) reports that the club's first flag (unofficially adopted) was a plain White Ensign without a Cross of St George in the fly, however, following official objections this was withdrawn and the club flew an undefaced Red Ensign ...

Flag of Royal Yacht Squadron. Grand Larousse Encyclopédique du XXe siècle (1928) says that the Royal Yacht Squadron is the oldest yacht club in the world. It was founded in 1812 and has its seat in Cowes, Isle of Wight. The King granted its members the special privilege to use the White Ensign. Ivan Sache, 25 December 2005

Learn about the history, design and usage of the White Ensign, the naval flag of the United Kingdom. Find out who can fly it at sea or on land, and see examples and photos of different versions of the flag.

Royal yachts have been a feature of the monarchy since at least 1660, [2] during this period command of the Royal Yacht was usually held by a captain. [3] The office of Flag Officer, Royal Yachts was established by letters patent on 15 October 1884. Royal Yachts was an independent command, administered personally by the Flag Officer, Royal Yachts. It was standard protocol for the (FORY) to be ...

The White Ensign is a naval ensign worn by British Royal Navy ships and shore establishments, with a red St George's Cross and the Union Flag in the canton. It has evolved from various striped and cross designs since the 16th century, and is also used by some other nations and yacht clubs.

This club was granted the use of the White Ensign in 1832 in circumstances which show how little the flag was valued at the time, and that its use was not regarded in any way as a privilege. Mr O'Connell, the original Commodore of that club, addressed a letter to the Admiralty dated the 30th January, 1832 which contain the following passage:-.

Wales [Fig. 4j. The flag is by no means unique, as the Royal Thames Yacht Club and'the Royal Yacht Squadron both preserve examples. Racing flags were rectangular flags, flown to indi cate that a yacht was taking part in a race. The practice has now fallen out of use by larger vessels owing to the amount of instrumentation carried at the ...

Royal Yacht Squadron. The Castle, Cowes, Isle of Wight, P031 7QT. Tel: +44 (0) 1983 292 191

Christopher Southworth, 28 March 2003. In 1955 the Admiralty reluctantly agreed that the flag of the Admiral of the Royal Yacht Squadron, a position held by the Duke of Edinburgh, might be flown at the foremast when he was on board Britannia in certain circumstances. I think that this is a St George's flag with a yellow royal crown in the centre.

The Royal Yacht Squadron; memorials of its members, with an enquiry into the history of yachting and its development in the Solent; and a complete list of members with their yachts from the foundation of the club to the present time from the official records. By Montague Guest and William B. Boulton Bookreader Item Preview

BRITANNIA RULES THE WAVES AND AMERICA WAIVES THE RULES. The Lipton era of competing for the America's Cup drew to a close upon his passing on the 2nd October 1931 after a summer of speculation that a sixth challenge would be forthcoming under the flag of the Royal Yacht Squadron to which he had finally been elected a member, earlier in the year.

Frequent reference to the Royal Yacht Squadron will be found elsewhere in this work, and under this particular heading no attempt can be made to give anything further than the merest outline of this club's history. ... Up to the year 1829 there had been several alterations in the flag flown by yachts belonging to the club, but in that year ...

Learn how Captain John C. Fremont, a U.S. Army explorer and trail blazer, led a group of settlers called Osos to revolt against Mexico in California in 1846. Find out how he organized the California Battalion and raised the Bear Flag over Sonoma.

The Yacht Club was founded in 1815 for Members to meet twice a year to dine and share their mutual interest in yachting. It had no premises so had no real need of officers; various Members chaired the bi-annual meetings in the early years before there was a Commodore, viz: Lord Grantham, Brydges Pope Blachford Esq, the Earl of Craven, Hon Charles Anderson Pelham Esq (later as Lord Yarborough ...

FILE — America's Cup skippers line up for a photocall behind The trophy outside The Royal Yacht Squadron in Cowes 20 August 2001. Over 200 boats, including vintage and J-class yachts, are ...

Learn about the 129th Rescue Wing, a California Air National Guard unit that performs search and rescue missions worldwide. The web page covers the unit's origins, aircraft, operations, and achievements from 1955 to 1993.

Get this The Los Angeles Times page for free from Sunday, August 8, 1897 os GriQcks Sunbcuj (Times. 2 SUNDAY, 'AUGUST 8, 1807.. Edition of The Los Angeles Times