- Yachting World

- Digital Edition

Donald Crowhurst: The fake round-the-world sailing story behind The Mercy

- October 2, 2019

The mysterious and tragic disappearance of the single-handed sailor Donald Crowhurst more than 50 years ago continues to fascinate. Nic Compton explains why...

Hailed as a round the world single-handed hero, Donald Crowhurst in fact never left the Atlantic during his 243 days at sea. Photo: Alamy

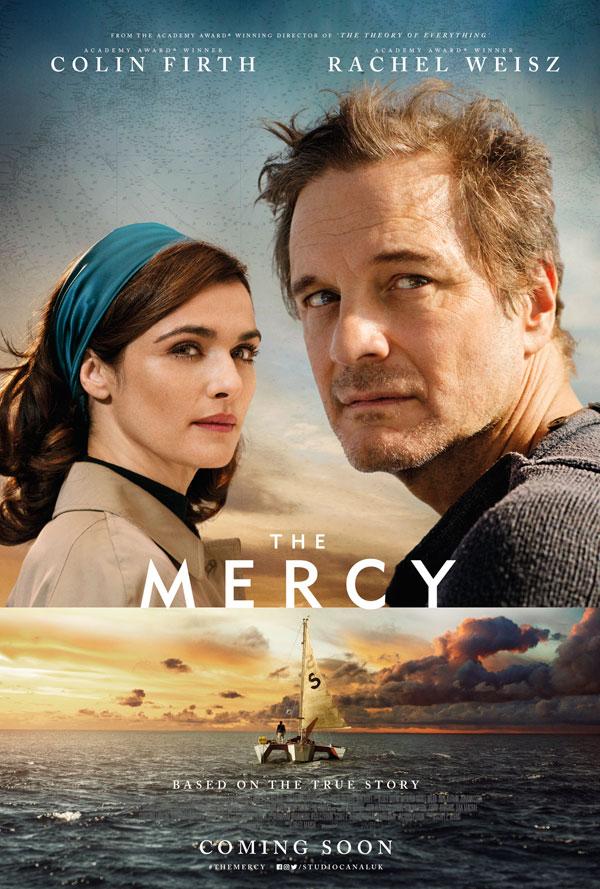

It was while I was researching my book about madness at sea in 2015 that I first heard a movie about Donald Crowhurst was in the works. Several websites published reports of a high-profile British feature starring Colin Firth and Rachel Weisz, and a few surreptitious photos of the cast filming off Teignmouth had been posted online. It seemed a lucky coincidence, given that my book would inevitably feature the Crowhurst story, but I assumed the movie would come out long before my book was ready.

Over the next couple of years, however, the release date for the film was repeatedly postponed – so much so that it became a running topic among Hollywood gossipmongers, who speculated that Crowhurst’s widow Clare had delayed progress, or that it was being held back to tie with the 50th anniversary of the events, or indeed that it might never be released in cinemas and go straight to DVD instead.

Meanwhile, I carried on writing my book, Off the Deep End , which was published in 2017, and the movie, The Mercy , was released in February 2018. There was never any doubt the tragic story of Donald Crowhurst would have to be included in any book about madness at sea.

Colin Firth stars as Donald Crowhurst in the 2018 film The Mercy . Photo: Studio Canal

Of all the stories I researched, it’s the one that has caught the public imagination most. Long before the latest Hollywood offering it inspired movies, books, plays, art installations, an epic poem and even an opera. Whereas many stories of adventures at sea seem to leave the general public cold, the Crowhurst tale continues to fascinate more than 50 years after Teignmouth’s most famous sailor vanished without trace. And yet, despite the thousands of words written about him, we really know very little more about him than we did 50 years ago.

It all started when Francis Chichester made his historic single-handed circumnavigation in 1966-67 – not the first to do so, by any means, but certainly the fastest up to that point, completing the loop in 226 days with just one stop, in Sydney, to repair his self-steering. Even before he’d docked at Plymouth there was a general realisation, which spread like osmosis throughout the sailing world, that the next step would be to sail around solo without stopping.

The challenge was turned into a contest by the Sunday Times which, in March 1968, announced two prizes: a Golden Globe trophy for the first person to sail round the world via the Three Capes single-handed and non-stop, and a £5,000 cash prize for the person to do it in the fastest time. The only stipulation was that competitors had to leave from a British port between 1 June and 31 October 1968, and had to return to the same place.

Article continues below…

A voyage for 21st Century madmen? What drives the Golden Globe skippers

A voyage for madmen, so was the original Sunday Times Golden Globe Race deemed. When the first non-stop race around…

How extreme barnacle growth hobbled the 2018-19 Golden Globe Race fleet

Eighty-knot gales, 10m-high waves, pitchpoling, loneliness and ever-depleting food reserves… of all the challenges facing a single-handed non-stop circumnavigator you…

Nine skippers eventually signed up for the race: the famous transatlantic rowing duo Chay Blyth and John Ridgway, who had by then fallen out but were sailing near-identical 30ft glassfibre production boats; Bernard Moitessier, already something of a legend in France for breaking the long-distance sailing record on his steel ketch Joshua; Moitessier’s friend Loïc Fougeron; Robin Knox-Johnston , an unknown British merchant navy officer sailing a heavy wooden boat called Suhaili ; two former British naval officers, Bill King and Nigel Tetley; the experienced Italian single-handed sailor Alex Carozzo; and Donald Crowhurst.

Out of the group, Crowhurst was by far the least experienced, the odd one out. Born in India in 1932, he went to Loughborough College after the war, until family nances and the death of his father forced him to cut his education short. He joined the RAF in 1948 but was chucked out after six years because of some high jinks with a vehicle; the same thing happened when he joined the army and he was forced to resign after he was caught trying to hotwire a car during a drunken escapade.

Persuasive character

Crowhurst with his wife Clare and their children Rachel, Simon, Roger and James, circa October 1968. Photo: Getty Images

Next he got as job as a travelling salesman for an electrics company, but was again dismissed after crashing the company car.

Ever-persuasive, he talked himself into a job as chief design engineer for an electronics company in Somerset, and in 1962 set up his own company, Electron Utilisation, to manufacture electronic devices for yachts.

The company got off to a good start, selling a simple but well-designed radio direction finder which Crowhurst dubbed the Navicator. Pye Radio invested £8,500 in the project, before getting cold feet and pulling out.

It quickly became clear that while Crowhurst was a charismatic personality and brilliant innovator he didn’t have the business acumen to run a successful company, and Electron Utilisation was soon in financial trouble.

Crowhurst managed to persuade local businessman Stanley Best to invest £1,000 to carry the company over what he assured him was a temporary lean period.

It must have been obvious to Crowhurst that he was heading for another failure. By now 35 years old, he could see the same pattern repeating itself, of high ambition thwarted by petty practicalities. Only, by now married to Clare with four children and living in a comfortable house outside Bridgwater in Somerset, the stakes were higher than ever.

His response to failure was to reinvent himself yet again. This time he would become a record-breaking sailor, a seafaring hero in the vein of Chichester: he would sail around the world single-handed – even though he had until then only dabbled in sailing, mainly on board a 20ft sloop called Pot of Gold . First, however, he needed a boat.

After failing to persuade the Cutty Sark Committee to lend him Gipsy Moth IV for the voyage, he decided a trimaran would be the ideal craft – despite having never sailed on one. To get the funding to build his dream boat he achieved perhaps the greatest coup of his life.

With Electron Utilisation going down the pan, his backer Stanley Best wanted his loan repaid, but Crowhurst managed to persuade him the best way to get his money back would be to fund the construction of the new boat.

A replica of the 41ft Teignmouth Electron used in the filming of The Mercy . Photo: WENN Ltd/Alamy

The crux of his argument was that he would use the trimaran as a test bed for his new inventions, and the publicity gained from entering the race would catapult the company to success. The sting in the tail was that the loan was guaranteed by Electron Utilisation, which meant that, if the venture failed, the company would go bankrupt.

To understand how he managed this turnaround you have to go back in time. Photos of Crowhurst make him look geekish and uncool to the modern eye. With his sticky-out ears, high forehead, curly hair, tie and V-neck jumper, he appears the epitome of the eccentric inventor.

But all the contemporary accounts describe him as a charismatic, vibrant personality, the sort of person who lights up a room when they walk in – as well as being extremely clever. In fact, his cleverness was his problem. He had the gift of the gab and, once persuaded of something, could talk anyone into believing him.

“This is important,” said his wife Clare. “Donald had this definite talent. He would say the most amazing things, but then no matter how crazy they seemed, he’d be clever and ingenious enough to make them come true. Always. This is a most important point about his character.”

Crowhurst’s widow, Clare, holds the last photograph taken of Donald with his family. Photo: Guy Newman / Alamy

Slow off the mark

So Crowhurst got the money for Teignmouth Electron , which was built by Cox Marine in Essex and fitted out by JL Eastwood in Norfolk. It’s a measure of how far behind he was that by the time the Cox yard started building the hulls towards the end of June, Ridgway, Blyth and Knox-Johnston had already set off on their round-the-world attempts. In the event, complications meant the launch date was delayed and even when Crowhurst finally set off on 31 October – just a few hours before the Sunday Times deadline expired – his boat was barely complete.

None of the clever inventions he had devised for the boat were connected, including the all-important buoyancy bag at the top of the mast, which was supposed to inflate if the trimaran capsized. His revolutionary ‘computer’, which was supposed to monitor the performance of the boat and set off various safety devices, was no more than a bunch of unconnected wires.

Worse still, he had had to borrow yet more money from Best to finish the boat, and had mortgaged his home to guarantee the loan. Crowhurst made a desultory figure scrambling about the deck of his trimaran as he set off on his great adventure – only to turn around within a few minutes to untangle his jib and staysail halyards, which were snagged at the top of the mast.

It was just the start of his troubles. After two days at sea, while still within sight of Cornwall, the screws started falling off his self-steering and, not having any spares on board, he had to cannibalise other parts of the machine to replace them.

A leaky boat

A few days later, halfway across the Bay of Biscay, he discovered the forward compartment of one of the hulls had filled up with water from a leaking hatch.

Soon, other compartments began to leak and, as he’d been unable to get the correct piping for the bilge pumps, his only option was to bail them out with a bucket. Then, two weeks after leaving Teignmouth, his generator broke down after being soaked with water from another leaking hatch.

“This bloody boat is just falling to pieces due to lack of attention to engineering detail!!!” he wrote in his log. A few days later he made a long list of jobs that needed doing and concluded his chances of survival if he carried on were at best 50/50. He began to think about abandoning the race.

But Crowhurst was in a triple bind. If he dropped out at this stage, not only would his reputation be destroyed but his business would go bankrupt and, perhaps worse of all, he and his family would lose their home. For all these reasons, giving up was not an option.

It soon became clear his estimates for the boat’s speed had been wildly optimistic: he had estimated an average of 220 miles per day, whereas the reality was about half that, on a good day. There was no way he was going to catch up with the other competitors or win either of the prizes, unless something extraordinary happened.

And so, just five weeks after setting off from Teignmouth, Crowhurst started one of the most audacious frauds in sailing history: he began falsifying his position. From 5 December, he created a fake log book, with accurately plotted sun sights, working back from imaginary positions.

To make it look convincing, he listened to forecasts for the relevant areas and wrote a fictional commentary as if he was experiencing those conditions. It was quite a feat of seamanship, and only someone of Crowhurst’s brilliance could have carried it off convincingly.

The great deception

After a few days’ practice he felt sufficiently confident to send his first ‘fake’ press release, claiming he’d sailed 243 miles in 24 hours, a new world record for a single-handed sailor. In fact, he’d actually sailed 160 miles, a personal best perhaps, but certainly no world record.

And so the great deception began. As Crowhurst slowly worked his way down the Atlantic, his imaginary avatar was already rounding the Cape of Good Hope and heading into the Indian Ocean. Gradually, partly through misunderstandings and partly due to the spin added by his agent back in the UK, Crowhurst’s positions became ever more exaggerated, until it looked like he might win the race after all.

Meanwhile, the real Crowhurst was pottering around the Atlantic – ‘hiding’ in exactly the same area he had, only a few weeks earlier, jokingly suggested a sailor might hide to falsify a round-the-world voyage. To make sure his radio signals weren’t picked up by the wrong land stations, he maintained radio silence for nearly three months, from the middle of January until the beginning of April, which he blamed on his generator breaking down again.

Teignmouth Electron was found drifting in mid-Atlantic, 700 miles west of the Azores, on 10 July 1969

Unbelievably, he even put ashore in a remote bay near Buenos Aires in Argentina to buy materials to repair one of the hulls, which had started to fall apart. Despite being greeted and logged by local officials, this rule-breaking stop remained undetected.

On 29 March he reached his most southerly point, hovering a few miles off the Falklands, 8,000 miles from home, before starting his ascent up the Atlantic.

Finally, on 9 April, he broke radio silence and exploded back into the race with a telegram containing the infamous line: “HEADING DIGGER RAMREZ” – suggesting he was approaching Diego Ramirez, a small island southwest of Cape Horn (in reality, he was just off Buenos Aires).

By this time Moitessier had had his ‘moment of madness’ and had dropped out of the race and was sailing to Tahiti ‘to save his soul’. The only other competitors left were Knox-Johnston, who was plodding slowly up the Atlantic and on track to be the first one home, and Tetley, racing in his wake to pick up the prize for the fastest voyage.

Rachel Weisz plays Clare Crowhurst in The Mercy

It seems likely that Crowhurst was planning to finish a close second to Tetley, which would save him from financial ruin without drawing too much attention to his fraudulent log books.

But his reappearance in the race had a dramatic effect on the course of events. Already nursing a broken boat up the homeward leg of the Atlantic, Tetley worried he might lose the speed record to the resurgent Crowhurst, and started pushing his trimaran faster towards the finish line. Some 1,100 miles from home, the inevitable happened: Tetley’s boat broke up and sank, and he had to be rescued by a passing ship.

Suddenly, the spotlight shifted to Crowhurst, the unlikely amateur who’d apparently come out of nowhere to beat the professionals. The BBC had a crew on standby to record his homecoming and hundreds of thousands of people were expected to throng the seafront at Teignmouth to welcome him home.

It was everything Crowhurst dreaded. As one of the winners, his books would come under much closer scrutiny – and indeed there were already some, including race chairman Francis Chichester, who suspected something wasn’t quite right.

In the middle of June, Crowhurst reached the Sargasso Sea and, as the tradewinds died and his boat slowed down, he descended into a mental quagmire of his own. It was as if all his previous failures had caught up with him in this one grand, final failure.

Teignmouth Electron on Cayman Brac in 1991. The wreck has deteriorated considerably since. Photo: Geophotos / Alamy

And this time there was no way out, no way of reinventing himself. Instead, he gave up ‘sailorising’ and resorted to philosophising instead. Over the course of a week, he wrote a 25,000-word manifesto that described how mankind had achieved such an advanced evolutionary state that it could now merge with the cosmos. All that was needed was ‘an effort of free will’.

He ended his journal on 1 July with this desperate appeal: ‘I will only resign this game / if you agree that / the next occasion that this / game is played / it will be played / according to the / rules that are devised by / my great god who has / revealed at last to his son / not only the exact nature / of the reason for games but / has also revealed the truth of / the way of the ending of the / next game that / It is finished / It is finished / IT IS THE MERCY’

There then followed a countdown, ending at 11:20:40 precisely. It’s not known what happened next, but it’s generally assumed Crowhurst jumped over the side of the boat to his death. His empty yacht was found by a passing ship on 10 July with two sets of log books on board: the real and the fake.

It was left to Sunday Times journalists Nicholas Tomalin and Ron Hall to piece together what had happened and to reveal to the world Crowhurst’s elaborate hoax. With Crowhurst and Tetley both out of the race, Knox-Johnston, on his slow wooden tortoise of a boat, was the only person to finish the race and was duly award both prizes – though he subsequently donated the £5,000 cash prize to Crowhurst’s widow.

Huge public interest

The Golden Globe race generated enormous public interest at the time, and the discovery of Crowhurst’s boat was front page news. It’s a fascination that has continued almost unabated to this day. The French film Les Quarantièmes Rugissants , based on the Crowhurst story, was released in 1982, while at least five plays have picked up the theme, as well as the 1998 opera Ravenshead.

In 2006, the acclaimed documentary Deep Water incorporated contemporary footage of the race, including some shot by Crowhurst during his voyage, and in 2017 director Simon Rumley released his own stylised take on the story, called simply Crowhurst.

The Mercy , then, is only the latest take on the Crowhurst saga – although with Colin Firth and Rachel Weisz on board, it is the most high-profile. So how does it compare to previous efforts?

As you’d expect of such a mainstream movie, the focus is firmly on the psychological drama rather than on the sailing – which is probably just as well considering how often films get the details of sailing wrong. There are some minor errors – Chichester wasn’t the first person to sail around the world single-handed, and the prize for the first competitor to finish the race was a trophy, not £5,000 – but the sailing scenes are generally quite convincing.

More importantly though, The Mercy is a captivating psychological drama, which shows how, through a series of small steps, a person can box themselves into a corner from which there is no escape. It’s this humbling of a deluded but essentially well-meaning man that gives the story such resonance and has inspired artists and writers for more than five decades. For, as anyone who has sailed out of sight of land knows, the sea has a knack of bringing out our inner demons. There is a Crowhurst in us all.

First published in the March 2018 edition of Yachting World. The Mercy is available to watch on BBC iPlayer until 11 Jan 2021 .

'It is the mercy'

Donald Crowhurst's last diary entry before he disappeared overboard. Carving by Tacita Dean

07 Feb 2018

The Mercy starring Colin Firth portrays Donald Crowhurst's tragic attempt to sail around the world single-handedly in the first race of its kind. Maritime specialist Jeremy Michell sheds light on the perils of sailing alone, the progress of yacht racing, and the importance of remembering failure.

By Kate Wilkinson

Visit the National Maritime Museum

The thrill of the race

Fifty years ago, the Sunday Times Golden Globe became the first solo non-stop round-the-world yacht race. Building on the international celebrity of Francis Chichester’s circumnavigation in 1966-67, the UK newspaper launched a sailing event to capture the world’s imagination – the ultimate competition of skill and endurance, and open to anyone, amateurs included.

'Yacht racing in this country has always been big, but it tended to be fairly elitist in the past,' says Jeremy Michell, a sailing instructor and part of the National Maritime Museum’s curatorial team, 'The Golden Globe opened up in a more popular mind the idea that people who are not wealthy could go and take part.'

Yachting really began when King Charles II brought his enthusiasm for the activity to England on return from exile in 1660 and raced yachts down the Thames against his brother for huge wagers. In the late 1870s, Lord Brassey achieved the first circumnavigation by a private yacht, building himself a steam-assisted three-masted schooner called 'Sunbeam' and sailing round the world with his family. The boat's figurehead is on display in the National Maritime Museum.

The Golden Globe opened up in a more popular mind the idea that people who are not wealthy could go and take part.

Struggling businessman and sailing amateur Donald Crowhurst was the classic underdog when he entered the 1968 competition. Putting everything into the race, he had signed a contract with his sponsor whose penalty clause meant that he would forfeit his house and business if he didn’t finish.

A doomed adventure

Crowhurst waved goodbye to his wife and four children on the race’s last eligible day aboard the Teignmouth Electron, a trimaran he had barely sailed before setting off. He had planned to equip the vessel with his own safety features, the success of which he hoped would revive his business in maritime navigational technology, Electron Utilisation Ltd. But he hadn’t completed the work before leaving British shores, leaving him in the process of tweaking while sailing.

It didn’t take Crowhurst long to realise how perilously ill-equipped he would be to tackle the waves of the Southern Ocean. If he continued he could die, but quitting would ruin him financially.

For a while it seemed like the plucky amateur could steal the race when Crowhurst started reporting false coordinates showing incredible gains in distance. The deception ended when after weeks alone at sea under immense physical, personal, and financial pressure, he committed suicide. This seemed the most likely cause of his disappearance: when rescuers found his abandoned trimaran, they discovered log books and reams of diary entries showing a collapsing mind.

Crowhurst’s tragedy caused a worldwide sensation. The Sunday Times Golden Globe didn’t run again, and its winner, Robin Knox-Johnston donated his £5,000 winnings to Crowhurst’s grieving family. Knox-Johnston was the only entrant to complete the race, with the other entrants forced to retire along the way.

Solitude at sea

Crowhurst’s behaviour was seen by many as foolish and reckless. He was certainly underprepared, and his false reporting put unnecessary pressure on his fellow competitors. One bad decision followed another, and he was soon lost in a nightmare predicament. How could he let things go so wrong?

Michell says it’s important not to underestimate both the physical and mental challenge of a solo voyage: 'Unless you have done that sort of race, it’s very difficult to make a judgement call as to what the trigger points are to make someone lose their mind in that way and potentially commit suicide.'

Alone at sea, you might catch about 20 minutes of sleep before you’re up again doing something. Performing the roles of a whole crew, you have to be mentally alert all the time. A small change of sound on the boat might wake you up.

Unless you have done that sort of race, it’s very difficult to make a judgement call as to what the trigger points are to make someone lose their mind in that way and potentially commit suicide.

Not only that, without anyone to talk to, 'you’ve got no one to relieve any emotional issues you might have, whether that’s frustration, anger, sadness, loneliness.' Michell knows those who have sailed long distances on their own. During one transatlantic voyage, a friend would call any ship he saw just for the sake of another voice (as well as to confirm his position with their navigation): 'He said you could end up in tears over the most stupid things because it’s the only emotional release you have.'

Though at home it might seem bizarre, when you’re on your own it’s a very different emotional experience, Michell says.

21st Century racing

Though the stakes are high, sailing around the world single-handedly continues to present an appealing challenge. Yachting is as popular as ever and there have been numerous successful racing events world-wide.

What has changed in yacht racing between now and Crowhurst’s day?

Michell lists the improvements to on board technology: the use of hydraulics to keep the yacht stable, electronic equipment for winches, hoisting and dropping sails. Most importantly, there’s the communication. Satellite telephones and beacons allow people to know where you are. In short, 'there’s a lot more of a safety net,' Michell says.

Today it would be unimaginable for a sailor of Crowhurst’s limited experience to take part in such a demanding voyage. The Vendée Globe, a single-handed non-stop round-the-world race founded in 1989, requires its entrants to undertake survival training before participating.

Commemorating failure

Royal Museums Greenwich plays host to some of the most dramatic, awe-inspiring, and successful maritime stories through the objects on display and in conservation. John Harrison’s 18th Century marine timekeepers in the Royal Observatory were the first instruments to solve the problem of finding longitude at sea.

Also in our collection is Donald Crowhurst’s ‘Navicator’ , which he produced and took with him on his doomed voyage. On free display in the Queen’s House is a series of striking photographs by artist Tacita Dean, of Crowhurst’s abandoned trimaran on the coast of the island Cayman Brac. In the National Maritime Museum you can find the artist's carving, of the words 'It is the mercy', which refer to Crowhurst's final diary entry.

So why do we preserve the memory of such a sad event in maritime history?

'It’s always good to remember that life isn’t one long successful winning streak,' Michell says, 'it was never obvious that Britain would be a top maritime nation: it happened through incidences, setbacks, circumstances, failures and successes. In terms of sailing and our yachting industry, it’s exactly the same.'

Crowhurst’s story is a useful reminder of the dangers of yachting, and would have made an impact on the regulation of similar racing events since 1968. 'Out of failure can come some kind of success that makes it safer for other people,' Michell says.

The race’s revival

2018 marks the 50th anniversary of that first ill-fated race. Following a number of books and documentaries over the years, Colin Firth plays Crowhurst in the upcoming film, The Mercy, which is set to fascinate audiences anew. In an earlier preview of the film last year, Robin Knox-Johnston expressed his satisfaction with the film in an interview with Yachting & Boating World magazine.

Later in the year, the Golden Globe race will be re-launched to test sailors under the same circumstances that Crowhurst and Knox-Johnston faced. No modern satellite technology is allowed for navigation – instead competitors must use their skills with instruments such as sextants to make the necessary calculations to steer a good course.

As a safety measure, the race’s website states that:

'All entrants will be tracked 24/7 by satellite, but competitors will not be able to interrogate this information unless an emergency arises and they break open their sealed safety box containing a GPS and satellite phone.'

Also unlike the original race, entrants must show prior ocean sailing experience of at least 8,000 miles and another 2,000 miles solo.

In July the competitors will set off for a challenge like no other.

Even after 50 years, the events of 1968 continue to both haunt and inspire the world’s imagination.

Banner image: 'It is the mercy' by Tacita Dean, courtesy of the artist and Frith Street Gallery.

Become a member

Member benefits include events such as the exclusive preview screening of The Mercy on 8 November, arranged with STUDIOCANAL, a day before the official cinema release.

Find out more

What really happened to sailor Donald Crowhurst on the voyage that inspired The Mercy?

Acclaimed director James Marsh reveals his theory about the tragic Brit played by Colin Firth

- Thomas Ling

- Share on facebook

- Share on twitter

- Share on pinterest

- Share on reddit

- Email to a friend

What sort of a man was Donald Crowhurst, the amateur sailor who set off around the world alone never to be seen again?

A vainglorious chump who abandoned his wife and four young children in reckless pursuit of his own impossible dream? Perhaps a man wounded by past failures who wanted to prove to that family he was worthy of their pride?

Or a delusional fantasist – someone whose desire to be noticed cost him his life, robbing his wife of a husband and his children of a father?

- The Mercy review: a compelling story told with care and compassion

- Colin Firth and Rachel Weisz on the harrowing true story behind new film The Mercy

Most likely, a little bit of all the above. Which is why Crowhurst’s life, and death, have so fascinated writers and filmmakers ever since he plunged over the side of his small trimaran during the first nonstop, round-the world yacht race in 1968-69 (a race ultimately won by the only finisher, Robin Knox-Johnston).

Here was a man who lied about his position in the race – a competition he was disastrously ill-equipped to take part in – realised his fraudulent actions would be uncovered and, rather than face the music at home, took his own life.

More like this

Or did he? Director James Marsh (a Bafta winner for documentary Man on Wire and the Stephen Hawking biopic The Theory of Everything) has another theory that extrapolates the written evidence found on Crowhurst’s boat, showing that the amateur sailor had totally lost his mind.

“Clearly, the pattern of agony you see in the logbooks suggests that he really is on a path to self-destruction, and that’s one very obvious way of interpreting what happens. The second is that it was simply an accident and he may have just slipped and fallen off the boat. And the third possibility is one that I think intrigued Colin and I more than anything else.

“We felt that in his final writings he was constructing a different version of reality for himself to enter into and he may well have believed he was going somewhere else when he stepped off the boat. But, clearly, the logbooks do suggest a huge mental crisis.”

The “Colin” in question is Colin Firth, who plays Crowhurst in Marsh’s new film The Mercy, a title that takes its name from the sailor’s maniacal final writings.

“The last words written in his logbook are ‘It is the mercy,’ which feels like a kind of idea of a release from all his torment,” says Marsh.

Both he and Firth would be the first to admit that this is a sympathetic evocation of Crowhurst’s decline and fall (his abandoned boat, the Teignmouth Electron, was found drifting in the mid-Atlantic more than eight months after he’d set off from south Devon).

Both feel that history has been unkind to him. “What you see is a man under enormous pressure,” says Marsh. “You know that he shouldn’t be going. He hadn’t prepared well enough and the boat was not fully seaworthy.”

But Crowhurst did put to sea. After struggling with faulty equipment, he fell behind in the race and, aided and abetted by his PR man back in Devon (brilliantly played by David Thewlis), began falsifying his race position.

The fact that Crowhurst was, as Marsh describes, “a good father and husband” makes the tragedy even more unsettling.

“That was what he betrayed,” says the director. “He doesn’t return to the people he loves because he can’t, and that has blighted their lives. I think some of that is the unravelling of his mind because of all those months of isolation at sea, and under the burden of these decisions that he’s made about cheating. I think he would say, ‘I’ve brought disgrace upon my family and maybe it’s better not to come back at all.’”

Crowhurst’s wife is played by Rachel Weisz. She says of her character, “I sense that Clare loved Donald very deeply and she didn’t want to stop him living out his dreams.”

The real-life Clare, now in her 80s, never remarried after her husband’s death and, remaining protective of his memory, is wary of the attention of this new film (in cinemas from Friday 9 February).

“I don’t think they’re particularly ready to welcome another telling of this tale, and who can blame them?” says Marsh. “It’s a private family tragedy that on a regular basis seems to get into the news, even after all these years. I don’t think it’s something that any of us would like if it were our family. But from what I can gather, they’ve seen the film and do regard it as a sympathetic telling of Donald’s story.”

Sympathetic it unquestionably is. But in attempting to rehabilitate the reputation of Crowhurst, is Marsh guilty of rewriting history?

“The thing is, I don’t think he was guilty of some grand conspiracy to cheat. He falls into it step by step, which is how most terrible things done by decent people tend to happen. You gradually get yourself into a situation that you can’t get out of. I really sympathise with that. I understood it from a personal point of view and wanted to give the most forgiving account of that process.

“If it were me, I would have turned back and gone straight to my family and said, ‘I’ll deal with the humiliation.’ There were contradictions that you can’t really reconcile, but that’s true of any complicated person.”

The Mercy is in UK cinemas now

- Discover the delightful South Devon town at the heart of The Mercy - Teignmouth

Subscribe to Radio Times

Try 10 issues for just £10!

FREE monthly prize draw!

Sign up to our reader offer newsletters and be entered into a monthly prize draw. August's prize is a Roberts Play 11 radio.

The truth about equity release

More and more homeowners are drawing cash from their property – Melanie Wright has the facts.

The best TV and entertainment news in your inbox

Sign up to receive our newsletter!

By entering your details, you are agreeing to our terms and conditions and privacy policy . You can unsubscribe at any time.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

In 'Deep Water,' a Sailor Who's Lost His Bearings

Kenneth Turan

Donald Crowhurst on his boat, the Teignmouth Electron , before he set out on the round-the-world sail that would threaten him with ruin. IFC Films hide caption

Donald Crowhurst on his boat, the Teignmouth Electron , before he set out on the round-the-world sail that would threaten him with ruin.

Watch 'Deep Water' Clips

(Requires RealPlayer )

Deep Water is disturbing, unnerving and wire-to-wire involving. It's the story of a dream that got so wildly out of hand that it ensnared the dreamer in an intricate trap of his own creation.

It all began in 1968, when The Sunday Times newspaper sponsored what was billed as the greatest endurance test of all time: a single-handed sail around the world, with no stops allowed and dangers at every point of the compass.

Almost all of the 10 men who announced that they would compete were top-notch sailors. And then there was Donald Crowhurst, amateur yachtsman and father of four, owner of a floundering marine electronics business who yearned for bigger things. As his son Simon explains in Deep Water , "he needed a challenge, to show who he was — and this, the greatest one possible, compelled him."

The sea itself was unforgiving, however, and once Crowhurst began his journey, his lack of preparation time led to serious problems with his 41-foot trimaran and the starkest possible choice: risking his life if he continued, financial ruin if he went back. Period, end of story.

The heart of Deep Water is a series of empathetic and perceptive interviews with the individuals who knew Crowhurst best. They've had decades to think about the story, which makes them candid, articulate and insightful.

If you want to know why documentaries are increasingly capturing audiences' imaginations, this is a good place to start. It's a story that couldn't possibly be invented, a tale that has the jaw-dropping twists and reverses only reality can provide.

Stay up to date with notifications from The Independent

Notifications can be managed in browser preferences.

UK Edition Change

- UK Politics

- News Videos

- Paris 2024 Olympics

- Rugby Union

- Sport Videos

- John Rentoul

- Mary Dejevsky

- Andrew Grice

- Sean O’Grady

- Photography

- Theatre & Dance

- Culture Videos

- Fitness & Wellbeing

- Food & Drink

- Health & Families

- Royal Family

- Electric Vehicles

- Car Insurance Deals

- Lifestyle Videos

- UK Hotel Reviews

- News & Advice

- Simon Calder

- Australia & New Zealand

- South America

- C. America & Caribbean

- Middle East

- Politics Explained

- News Analysis

- Today’s Edition

- Home & Garden

- Broadband deals

- Fashion & Beauty

- Travel & Outdoors

- Sports & Fitness

- Climate 100

- Sustainable Living

- Climate Videos

- Solar Panels

- Behind The Headlines

- On The Ground

- Decomplicated

- You Ask The Questions

- Binge Watch

- Travel Smart

- Watch on your TV

- Crosswords & Puzzles

- Most Commented

- Newsletters

- Ask Me Anything

- Virtual Events

- Wine Offers

- Betting Sites

Thank you for registering

Please refresh the page or navigate to another page on the site to be automatically logged in Please refresh your browser to be logged in

Drama on the waves: The Life And Death of Donald Crowhurst

In 1968 an amateur sailor set off on the inaugural solo round-the-world yacht race. incredibly, he appeared to be leading the race until the closing stages when he disappeared and was never seen again. now the tragic truth about this very british hoaxer is being told. ed caesar reports, article bookmarked.

Find your bookmarks in your Independent Premium section, under my profile

For free real time breaking news alerts sent straight to your inbox sign up to our breaking news emails

Sign up to our free breaking news emails, thanks for signing up to the breaking news email.

For the past week, Britain has been in the thrall of an extraordinary sporting challenge. Within 24 hours of the start of the Velux 5 Oceans, a three-stage solo round-the-world yacht race starting in Bilbao, four sailors were forced to return to port, so horrific were the conditions off the coast of Spain. It was a reminder, if one were needed, that a solo circumnavigation of the globe remains the Everest of sporting achievements. Sir Robin Knox-Johnston - who, at 67, is the Velux 5 Oceans' oldest competitor - called the Bay of Biscay's 40ft waves and high winds "boat-breaking".

He should know. In 1969, without the global positioning systems, or support crews, or the corporate sponsorship with which modern single-handers put to sea, Knox-Johnston became the first person to complete a non-stop solo circumnavigation on his boat Suhaili, winning the inaugural Sunday Times Golden Globe Race in the process. "In 1969, my only advance weather system," said Knox-Johnston last week, "was a barometer from the wall of a pub".

But as remarkable as Knox-Johnston's feat was, it will forever be eclipsed by the plight of one of his fellow competitors in that first race: Donald Crowhurst, a 36-year-old English businessman, who went to sea in a leaky boat and committed suicide in the Atlantic 243 days later. Now, splicing harrowing onboard audio and visual footage of Crowhurst with interviews of the sailor's friends and family, a film, Deep Water, tells the story of Crowhurst's last voyage, and his descent into madness.

A former RAF pilot with a small, ailing electronics business called Electron Utilisation, Crowhurst was, at best, an enthusiastic weekend sailor. He was also married and a father of four children. So what convinced him he should go to sea for nine months is anyone's guess. But not only was Crowhurst determined to enter the race, he was determined to win.

To understand Crowhurst's peculiar obsession with competing in this gruelling race, one needs to know that in 1968, Britain was in the grip of sailing fever. The previous year, Sir Francis Chichester had achieved the then monumental feat of sailing around the world, on his own, punctuated only by a stop in Australia. In the era of the space race, when the possibilities of human endeavour seemed limitless, the world lapped up the heroism of Chichester's achievement, and 250,000 people lined the south coast to cheer him home.

The Sunday Times, which had reaped the rewards of sponsoring Chichester's journey, was looking for a way to continue tapping into the appetite for maritime derring-do. The Sunday Times Golden Globe Race was born. Using the clipper route, from Britain, through the Atlantic and round the Cape of Good Hope; through the Indian and Pacific Oceans; round Cape Horn and back to Britain, the competition was billed as a test for the world's greatest yachtsmen.

But, to encourage entrants, no evidence of sailing experience was required, and competitors were allowed to set off any time before 31 October. A trophy for the first man to complete the course, and a separate prize of £5,000 for the fastest time, would be awarded. Out of the nine men who set off in 1968, only one, Knox-Johnston, finished.

Crowhurst's bid to win the Golden Globe always looked precarious. In the months before the race, the businessman had become convinced that by coupling a new, triple-hulled boat design with his own technological innovations (a self-righting mechanism in case of capsize, for instance), he could win. With the financial support of a local businessman, Stanley Best, Crowhurst bought and developed his vessel. But Best's money came with a proviso: if Crowhurst failed to finish the race, he would have to pay for the boat himself.

To make matters more complicated for Crowhurst, he fell into the hands of one of Fleet Street's more manipulative press officers, Rodney Hallworth, who knew Crowhurst was journalistic manna. Hallworth sold him to the press as a plucky, English amateur with incredible prospects of bringing home the big prize. All the while, the deadline for starting the race, 31 October, was creeping round, and Crowhurst was struggling to make his boat, the Teignmouth Electron, seaworthy.

The day before his voyage began, Crowhurst made last-minute preparations on the Electron, then retired to a hotel with his wife, Clare. That night, he broke down in tears. The boat, he knew, was not ready. But he also knew it was too late to pull out. Hallworth would not allow it. Best would want his money back. The family would be ruined.

Crowhurst set sail the next day with unsorted provisions and vital equipment strewn across the deck of the Electron. And, even at this early stage, calamity loomed. He was forced to return to harbour in the first minutes of his journey when an anti-capsize air-bag got caught in the rigging.

Over the next two weeks, Crowhurst made slow progress. As Knox-Johnston and the Frenchman, Bernard Moitessier, who had set off weeks earlier, neared New Zealand, Crowhurst was languishing in the North Atlantic. At least he was afloat. Four men - John Ridgway, Loick Fougeron, Bill King and Alex Carozzo - retired before they reached the Indian Ocean. Of the four who remained, one Englishman, Chay Blyth, who set off with no sailing experience, retired in East London, South Africa. Another, Nigel Tetley, was making good time ahead of Crowhurst.

But if Crowhurst's slow times were worrying, they were as nothing compared to the anxiety he felt about the state of his boat. The Electron had started to leak, and her skipper faced a dilemma. Should he continue into the Southern Ocean, where his boat would almost certainly sink? Or should he return home to face shame and financial ruin?

In the end, Crowhurst did neither. Instead, he started to radio a series of incredible positions and speeds to Hallworth, who, in turn, embellished the lies and sold them to Fleet Street as fact. Suddenly, Crowhurst seemed to have a genuine chance of scooping the prize for the fastest circumnavigation.

The truth was that the difference between Crowhurst's real and stated positions was growing by the day, a discrepancy he kept track of by recording two logbooks. But this ruse only exacerbated his problems. Because of the frailty of the Electron, Crowhurst could not enter the perilous Southern Ocean. Neither could he return home, where ignominy and bankruptcy awaited. All the while, his wife, his four young children, and the rest of the world thought he was sailing into the record books.

Faced with an insoluble problem, Crowhurst did the only thing he could think of; he stayed put. Bobbing around in the Atlantic off Brazil, Crowhurst scrupulously filled out his fraudulent logbook, and cut off all radio contact with the world for three months. At one point, he was forced to pull into an Argentine fishing port to make vital repairs to his boat, an action that in itself would have been enough to disqualify him from the race. Still, Crowhurst kept up his pretence.

His fellow competitor, Moitessier, disillusioned about competing in a commercially motivated event, had rejected the idea of finishing the race at all. Instead, he simply to kept on sailing, eventually dropping anchor in Tahiti, after one and a half laps of the globe. Knox-Johnston arrived back in England to a hero's welcome. He had won the trophy for coming in first. But he had made slow time, a leisurely 312 days. In the eyes of the world, the race was now on between Tetley and Crowhurst to see which man would win the race for the £5,000.

The thought of winning terrified Crowhurst. He knew that if he came home in the fastest time, his logbook would be subject to scrupulous checks by the Golden Globe judges and the press. He determined on making a slow journey across the Atlantic, so Tetley would win the prize, and he could come in a dignified, unheroic second. Re-establishing radio contact with Hallworth for the first time in 12 weeks, Crowhurst confirmed he would not be able to catch Tetley. Still, his family and friends, who had been fearing the worst for Crow-hurst, were relieved that he was, apparently, safe and well.

Crowhurst's scheme was looking good. In May 1969, he began to make for home, his faked journey matching his real one for the first time in months. Then, disaster. Tetley, thinking Crowhurst was hot on his heels, had pushed his boat too hard, and sunk in the Azores. Crowhurst was going to win the prize.

The news of Tetley's sinking affected Crowhurst profoundly. He drifted deep into depression, refusing to sail, and took to his logbook. As he lolled in the mid-Atlantic, Crowhurst wrote a 25,000-word treatise on time travel and divinity. He counted down his remaining hours on Earth, believing death would not only be "the mercy" but that it would transform him into a "cosmic being". On 29 June 1969, after 243 days at sea, Crowhurst made one last entry into his logbook. His self-allotted time had come. This was "the mercy" he had been praying for. His boat was found 12 days later, with logbooks recording his genuine position and grainy sound and video recordings unharmed. It has since been assumed Crowhurst took the logbook of his fraudulent positions with him as he threw himself overboard. Back in Britain, Knox-Johnston was awarded the £5,000 for the fastest time, which he donated to the Crowhurst family, and Tetley was given a consolation prize. For unknown reasons, Tetley committed suicide a year later.

Deep Water's co-producer, Al Morrow, said: "What I felt about Donald was that although not all of us would go to sea, the situation was one that any of us could have got ourselves into. You tell one tiny little lie, and that turns into another lie, and suddenly there's no way out. The other thing that really struck me about the story is that being on your own for nine months at sea is such a unique thing. You have no one to speak to. He must have been so lonely."

Her fellow producer, Jonny Persey, added: "I recognise [Crowhurst's story] could arouse feelings of anger. He could have done the right thing any number of times. He had those opportunities, but every decision he made was wrong. It was very hard for his family to contribute to this film, but they have come to a point where they understand what happened, and recognise the complexity of what was going on with Donald."

The first screening of Deep Water, with the creative team and the family, was a charged occasion, says Morrow. "I was terrified," she admits. "The family had been so supportive through the process, but they had to trust us with the direction the film was going in. Clare's daughter, Rachel, walked out a few times in the screening, because she found it too emotional to sit through."

Another person in whom Deep Water will strike a resonating chord is Knox-Johnston, himself an interviewee for the film. Unable to attend any preview screenings, he has taken a DVD of Deep Water on his Velux 5 Oceans boat, Saga Insurance. When he finds a spare two hours away from racing, he will watch Crowhurst's story, all alone at sea.

Deep Water is released on 15 December

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

New to The Independent?

Or if you would prefer:

Hi {{indy.fullName}}

- My Independent Premium

- Account details

- Help centre

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

- Privacy Policy

- Copyright and DMCA Notice

Donald Crowhurst and his Fatal Race Round the World

In 1968, British newspaper The Sunday Times sponsored the first ever round-the-world yacht race. Guaranteed excellent publicity from the paper, nine contestants enlisted, drawn by the glamor of winning such a race, as well as the £5,000 prize for the fastest time (as much as $120,000 today).

The race was well organized but there were several safety concerns. Yachts were to be manned by a single person only as the race was a solo one, and the race would be non-stop. Competitors could not be vetted thoroughly on the safety of their boats and their abilities as sailors , and there were no entry requirements.

Competitors could start the race at any point between 1 June and 31 October 1968. One such competitor, who set off on the very last day, was Donald Crowhurst.

An Ambitious Man

Donald Crowhurst was not a professional sailor but had some knowledge and experience about sailing. He was an inventor and electronics engineer, and hoped to use this to his advantage during the race.

To aid in his navigation, he created a radio-direction finder that he named “Navicator” and he would make the attempt in a very unusual boat design, a trimaran called the Teignmouth Electron . Trimarans could theoretically travel much faster than monohull boats, but had not been tested on such a grueling expedition.

Crowhurst hoped to stabilize his business with the publicity and money that he would get by winning this race, but the upfront costs were steep. To take part, he raised financing from some businessmen and mortgaged his home as well.

This allowed him to finish work on the Teignmouth Electron which he had constructed specially for the voyage. The boat-builder promised Crowhurst that the boat would be speedy but warned about stability issues in heavy seas.

But on the first sea trial of the boat, a few noticeable problems came up. The deadline was rapidly approaching and it wasn’t possible for Crowhurst to equip new parts and repair the vessel properly to make it ready for the race.

- The Sarah Joe Mystery: Disappearance in the Pacific

- SS Baychimo: Ghost Ship of the Arctic

He only had two ways and was faced with a dire choice: either sail and take part in the race with a doubtful boat, or give up to face bankruptcy and humiliation. Crowhurst, fatefully, took the first option, setting sail in a boat untested in either design or practice.

The Race Begins!

Just like the boat wasn’t ready, the weather wasn’t favorable for the race as well. Clare, Crowhurst’s wife, suggested to him not to take part in it, as there was a great risk. But as she saw Crowhurst sobbing with the thought of humiliation, she and their four kids tried to make Crowhurst believe he could do anything. They didn’t want him to regret the thought of giving up.

On 31st October 1968, the weather miraculously calmed and gave Crowhurst his opportunity to start the voyage. Crowhurst kissed the forehead of each of his children and asked the elder ones to take care of their mother, and launched the Teignmouth Electron .

Soon after the race began, Crowhurst observed that the boat was already leaking like a sieve. And he realized right at that moment that this boat wouldn’t be able to take the blow from 30 or 40-foot (9 – 12 m) waves in the Southern Ocean , writing in the logs that the ship would probably sink once it entered heavy seas.

Trapped and with no options left, Crowhurst started to come up with a plan! He didn’t want to give up and live with humiliation forever, he would rather cheat than lose.

The Crooked Plan of Donald Crowhurst

GPS didn’t exist back then, and so the only way of checking the position of the boats after the race was through a review of the logbooks and the charts carried on each boat. Donald Crowhurst intended to use this to his advantage, saving his boat and completing the race.

Therefore, he started sending radio messages to the organizers giving false positions. He charted a false course down into the south Atlantic, and then, fearing his transmissions might give him away, he then disconnected the radio contact completely off the coast of Brazil .

Even these waters were too much for the T eignmouth Electron . His boat was so damaged at one point that he had to stop at a fishing port in Argentina to make some necessary repairs.

Crowhurst’s plan was to maintain two logbooks, one for his real journey and one for his fictitious race experience. The pressure of keeping two logbooks would have been extreme, and was made worse when he realized that his fictitious log wouldn’t be justifiable at close scrutiny if he won the race.

- Taken by the Ice: What Became of the Franklin Expedition Crew?

- Amelia Earhart’s Last Flight – Mystery at Sea

The logbooks would need to contain weather conditions during the course of his voyage. Crowhurst had no idea what the weather was like where he was supposed to be, and the fictitious log reflects some of this in its hazy descriptions.

Claiming to be making good time, Crowhurst wandered in the Atlantic until, finally, his made-up voyage started to catch up to his actual position. At this point the race leader was Nigel Tetley, who was making excellent time. Crowhurst intended to let Tetley win, with himself coming second to avoid much of the log-book scrutiny.

In May 1969, Donald finally turned back for home. But again he had miscalculated, as his apparent pace panicked Tetley. Forced to race at breakneck speed to keep up with Crowhurst’s apparent pace, Tetley’s boat failed and he capsized .

This meant Crowhurst was now far in the lead and on course to get the £5,000 prize for being the fastest competitor. With this victory he felt sure his cheating would be exposed.

After 243 days at sea, Crowhurst made his last entry in his logbook on 1st July 1969. He wrote, “It is finished, It is finished. It is the mercy.” And that was the last anyone heard of Donald Crowhurst.

Lost at Sea

12 days after his last logbook entry, the Teignmouth Electron was found drifting in the ocean . There was no sign of Donald Crowhurst. It was believed that he had jumped off the boat with his fictitious logbook, leaving behind the actual one on the deck by way of confessing his sins.

Crowhurst’s wife maintained that he would never commit suicide, but the evidence of the logbook was telling. He had hoped to become a British folk hero who conquered the seas, but in the end his sin was that of pride.

And so his life ended, trapped by his lies. Here was a man who believed he could sail across the world but couldn’t even make it past the Atlantic, and who believed he could fool the world, but ultimately left nothing behind but his confessional logbook.

Top Image: Donald Crowhurst never made it home. Source: hikolaj2 / Adobe Stock.

By Bipin Dimri

They Went To Sea In A Sieve, They Did. Available at: https://www.sportsnet.ca/more/big-read-donald-crowhursts-heartbreaking-round-world-hoax/

The Mysterious Voyage of Donald Crowhurst. Available at: https://howtheyplay.com/misc/The-Mysterious-Voyage-of-Donald-Crowhurst

The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst. Available at: https://jollycontrarian.com/index.php?title=The_Strange_Last_Voyage_of_Donald_Crowhurst

Bipin Dimri

Bipin Dimri is a writer from India with an educational background in Management Studies. He has written for 8 years in a variety of fields including history, health and politics. Read More

Related Posts

Lake superior’s three sisters: myth or deadly reality, jimmy carter, and his encounter with a ufo, majestic 12: the truth behind the men in..., padre pio stigmata, miracle worker or fraud, what happened to the zebrina ghost ship of..., agatha christie’s disappearance: amnesia, suicide, or despair.

- Cast & crew

- User reviews

The incredible story of amateur sailor Donald Crowhurst and his solo attempt to circumnavigate the globe. The struggles he confronted on the journey while his family awaited his return is on... Read all The incredible story of amateur sailor Donald Crowhurst and his solo attempt to circumnavigate the globe. The struggles he confronted on the journey while his family awaited his return is one of the most enduring mysteries of recent times. The incredible story of amateur sailor Donald Crowhurst and his solo attempt to circumnavigate the globe. The struggles he confronted on the journey while his family awaited his return is one of the most enduring mysteries of recent times.

- James Marsh

- Scott Z. Burns

- Colin Firth

- Eleanor Stagg

- Rachel Weisz

- 66 User reviews

- 104 Critic reviews

- 60 Metascore

Top cast 62

- Donald Crowhurst

- Rachel Crowhurst

- Clare Crowhurst

- Waterskiing Girl

- Dennis Herbstein

- Ronald Hall

- Sir Francis Chichester

- Mrs. Hughes

- James Crowhurst

- Simon Crowhurst

- Ian Milburn

- Sara Milburn

- Stanley Best

- Rodney Hallworth

- Ian Wheeler

- Chamber Member

- (as Richard Blaine)

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

More like this

Did you know

- Trivia At age 55, Colin Firth was 20 years older than Donald Crowhurst was when he set off on the Golden Globe race.

- Goofs When the Teignmouth Electron is leaving harbour, the yachts in the background have a stern shape that's about 40 years too modern.

Sir Francis Chichester : A man alone on a boat is more alone than any man alive.

- Connections Featured in Projector: The Mercy (2018)

- Soundtracks Maria Elena Written by Lorenzo Barcelata Performed by Los Indios Tabajaras

User reviews 66

- jamesowen-2

- Jan 3, 2021

- How long is The Mercy? Powered by Alexa

- February 9, 2018 (United Kingdom)

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Official Facebook (Australia)

- Official Facebook (UK)

- Teignmouth, Devon, England, UK (Exterior)

- StudioCanal

- Blueprint Pictures

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

- $18,000,000 (estimated)

Technical specs

- Runtime 1 hour 52 minutes

- Dolby Digital

Related news

Contribute to this page.

- See more gaps

- Learn more about contributing

More to explore

Recently viewed.

- Yachting Monthly

- Digital edition

‘It is the Mercy’: Donald Crowhurst’s log

- September 10, 2008

See inside Donald Crowhurst's logbooks

“I am what I am and I see the nature of my offence…”

October’s Yachting Monthly contains a 10-page special on the voyage of Donald Crowhurst, 40 years after the event. Click on the links below to see inside his logbooks.

Spread 1 Spread 2 Spread 3 Logs courtesy Pathé Films.

- AMERICA'S CUP

- CLASSIFIEDS

- NEWSLETTERS

- SUBMIT NEWS

Deepwater – the story of Donald Crowhurst

Related Articles

- Classic Galleries

Where in the World Is Robert Garside? As he races to lay claim to the first around-the-world run, Britain's Robert Garside is losing ground to a growing pack of skeptics

- Author: Franz Lidz

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ORIGINAL LAYOUT

Of all the great hoaxes in sporting history, few were more devious than the one perpetrated by Donald Crowhurst, the yachtsman who convinced the world he was circumnavigating it. In 1968 the 36-year-old electrical engineer from Great Britain set out to win the first nonstop solo round-the-world race. Though his radio reports to race officials suggested he was making great progress, he had gone off course and was bobbing listlessly in the South Atlantic, all the while faking a ship's log designed to prove he had girdled the globe. Faced with exposure if he returned home, he decided never to go back. In the end he left himself two options: Stay at sea forever or kill himself. He chose option number 2.

Robert Garside has spent the last six years telling the world he is jogging around it. In a bid to complete the planet's first solo loop and claim a place in Guinness World Records, the 35-year-old Englishman maintains that he has covered more than 30,000 miles and six continents. In December 1996 he set out from London's Piccadilly Circus, to considerable fanfare, with only $30 in his pocket and a 17-pound pack on his back. Since then Garside says he has traversed mountains, jungles and deserts, been shot at by gypsies in Russia, pelted with stones in India, jailed as a suspected spy in China and pounced on by thieves in Panama. Scores of newspapers, magazines and TV news shows have breathlessly reported how the astounding Garside lives a hand-to-mouth existence, persevering through donations and sheer pluck.

"During my travels I must have woken up 70 or 80 times regretting I was alive," he says, "but I've never once contemplated suicide. As hard as this odyssey has been, apparently it's what I've opted for in life. It's my claim to fame."

Well, not exactly. Runningman, as the former psychology student calls himself, has been on the run from critics since late 2000, when Canadian journalist David Blaikie accused him of making fraudulent claims about his journey. On his Ultramarathon World website (ultramarathonworld.com), Blaikie detailed inconsistencies in Garside's own Internet accounts and questioned how a man with little ultrarunning background and no logistical support could run what amounted to nearly a marathon a day for not just days and days but years and years.

With doubts about his mighty feats mounting, Garside admitted in February 2001 to having skipped thousands of miles in 1997 during the Eurasian leg of his journey and having made up a dramatic trek through Afghanistan and harrowing encounters with Pakistani bandits in his Web diary. Both yarns, he confessed, were cooked up in London--he had hopped on a plane in Moscow and flown home to be with his then girlfriend. These "little white lies" (Garside's words) have led to bigger and grayer ones (he has been forced to retract claims for, among other things, the British and world distance records), so that now nobody knows what, if anything, he says is true.

No one disputes that Garside has racked up many, many miles on his trek. The question is, how many has he missed? "Robert has deluded himself into believing that he has not cheated," says Tokyo-based journalist Peter Hadfield, an early ally who has soured on him. "Every time his fabrications are exposed, he invents a new story and convinces himself it is true. When his cover is blown again, he invents another story and then convinces himself of that."

Like Crowhurst, Garside is the kind of flawed self-mythologizer you find in Joseph Conrad novels. Unlike Crowhurst, he's still plugging along. After the scandal broke, Garside retroactively rerouted his journey. The miles he logged from London to Moscow would not count toward the record; instead he considered New Delhi--where he resumed his eastward run in late '97--to be the official starting and ending point. In Spain, as of last week, he hopes to reach the finish line, the India Gate arch, by the end of this year. Upon entering the sacred city, he says, he expects to be joined by "500 Hindu runners" and be hailed as a hero. "He will not get there," predicts British photo agent Mike Soulsby, Garside's principal patron (to the tune of more than $10,000) since '97. "I had thought Robert was credible but now realize I have been totally and utterly conned. He's a miserable little two-faced shyster."

That isn't to say Garside is without redeeming qualities. "He could've achieved so much because his drive and determination are incredibly strong," says Hadfield. "Instead, it's his lack of moral character--his readiness to deceive--that's destroyed him."

Garside shrugs and says, "There's an expression in England: You can't get anything in life without pissing a few people off."

On a sun-baked June afternoon Runningman is minimizing the enormity of his deceit at a cafe on the east coast of Spain. He has been hanging out in Valencia with his girlfriend, Endrina Angarita Perez, and working the phones. To bankroll what he calls his "mission," Garside badgers and wheedles everyone from sunglasses salesmen to magazine photo editors.

The bistro is an egg toss from Parque Gulliver, a circular playground dominated by an enormous man-mountain of slides and chutes pinned to the ground by ropes. The Lilliputians are children, who scamper in and out of Gulliver's hollow body and scramble over his limbs. "At times I feel like Gulliver," says the harried globetrotter, who believes the skeptics want to entangle him in myriad discrepancies to keep him tied down and off the road. "A run around the world has never been done, and frankly, it scares people," he continues. "They can't handle the idea. Neither can I. But I am living this nightmare until India, and I hope that I will arrive without a psychological disorder."

Round-shouldered and thin, Garside has a white, hard face and colorless eyes. An air of befuddled sadness clings to him. He can be charming and chirpy until confronted with one of his little white lies. Thrown off script, he becomes monosyllabic, graceless, bitter.

Though Garside argues that "words can't hurt," they certainly get under his skin. Mention Blaikie, who tracks his movements as relentlessly as Javert dogged Jean Valjean, and Garside's nostrils twitch as if at an offensive smell. "Blaikie is my Osama bin Laden," he says with righteous indignation. "I've been watching this terrorist every step of the way. This faceless coward is conducting psychological warfare, testing me. You're not supposed to write such things based on theory. You write on evidence."

Garside says his own evidence--which he says is in storage at his mother's home in Slovakia--proves Blaikie launched a mass e-mail and phone campaign to discredit him and "sent out Ultramarathon World Taliban posing as journalists" to disrupt his press conferences. In retaliation Garside made abusive phone calls to Blaikie's home, including 26 in a single evening in early 2001. "I have the moral right to call up this cold, cognitive bastard a million times and keep him up all night and ruin his life," Garside says. "He's ruined mine."

Told that Blaikie denies dispatching any mass e-mails, Garside sputters, "Hello! That's absurd! Why...why...it's got to be Blaikie. Who else could it be?"

There's a flash of panic behind his eyes, but he gets a grip on himself to say, "The truth is, my run is too much of an outlandish, wild, wonderful thing to believe. That's why I'm being persecuted. People have been persecuting me my whole life, here and there in all sorts of ways."

Since leaving home at age 17 after a falling-out with his father, Garside says he "has just been trying to survive." Alas, his survival instincts have reduced an improbable run to a series of impossible journeys. Asked why he pretended his run had continued unbroken across Asia, Garside says impishly, "I was naughty. I shot myself in the foot."

He blew off a few more toes last year when he admitted to lying about running from Russia into Kazakhstan in 1997; in truth, he said, he turned back at the Kazakhstan border. He now says that the run ended several hundred miles before, in Moscow, and that his subsequent hiatus in London lasted not seven weeks, but six months. It was only after Garside's girlfriend dumped him and he chose not to return to his college, Royal Holloway University, that he flew to India to begin his quest anew. The fictional passages in his diary at www.runningman.info were a "psychological tactic" intended to convince potential competitors that he was too far along to catch. "When you're running around the world," he says, "you do anything to survive."

Anything includes duping the media in both Japan and Australia by announcing in 1998 that he had broken the world distance record, neglecting to mention the fact that he had started over in India. "If you added all my distances together," says Garside, "I would have set the record."

Anything includes asserting that in 1999 he jogged the 700 miles from Brasilia to the Brazilian city of Maraba in two weeks, averaging 50 miles a day with gear in tropical heat along a clogged highway. Implausible, carp Garside's critics. "Bad p.r. doesn't mean a damn thing," he insists and insists and insists. "Who cares?"

Guinness, perhaps. Before he began, Garside was told that to qualify for the record he simply had to travel 18,000 miles over at least four continents--presumably finishing at the same longitude at which he began. As proof of his run, Garside says, he's gathering witness statements, log books and time-coded videotape that he has shot roughly every hour. He plans to submit this evidence to Guinness after he finishes.

But Andy Milroy, who has been authenticating ultramarathon claims for Guinness for 25 years, cautions, "On tape, one bit of jungle, one bit of shrub, one bit of road looks like any other. You could be anywhere." Which is why it's important to have a support team (Garside doesn't) and map out your route in advance for the public (Garside won't). Milroy says there's another important criterion: a runner's credibility.

So, what if Garside gets to India and Guinness rejects his claim? Runningman puts his head in his hands and groans alarmingly. "My God!" he says. "I fear for this world if I'm denied the record. The Taliban will have taken over. That would be the biggest con in history."

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP MEXICO CITY

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP LONDON

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP TIBET

COLOR PHOTO: RUPERT THORPE HOLLYWOOD

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP PORTO ALEGRE, BRAZIL

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP BUENOS AIRES

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP SHANGHAI

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP RIO DE JANEIRO

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP KIMBA, AUSTRALIA

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP PENINSULA DE NICOYA, COSTA RICA

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP TOKYO

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP AGRA, INDIA

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP OUTSIDE GRECIA, COSTA RICA

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP VALENCIA, SPAIN

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP LA BOCA, ARGENTINA

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP HOKKAIDO, JAPAN

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP NEW DELHI

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP MANAUS, BRAZIL

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP CARACAS

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP PUNTA ARENAS, CHILE

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP MINSK, BELARUS

COLOR PHOTO: ESTEBAN FELIX/AP STRINGING 'EM ALONG Garside had been running for nearly four years before journalists started tying him in knots.

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP LHASA

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP PENINSULA DE NICOYA

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP SYDNEY

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP MANAGUA, NICARAGUA

COLOR MAP: MAP BY STEVE STANKIEWICZ REMAINING RUN COMPLETED RUN FERRIED VIA AIR/WATER Since restarting his journey in India in 1997, Garside says, he's followed the route above in his quest to complete the first around-the-world run. Now in Spain, he has 5,000 miles left in his run, which will likely take him across the Arabian Peninsula to the finish, under the India Gate.

COLOR PHOTO: PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF ROBERT GARSIDE/FSP MOSCOW

COLOR PHOTO: PAUL HACKETT/REUTERS LONDON

"Blaikie is my Osama bin Laden. I've been watching this terrorist every step of the way. This coward is conducting psychological warfare."

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Donald Crowhurst. Donald Charles Alfred Crowhurst (1932 - July 1969) was a British businessman and amateur sailor who disappeared while competing in the Sunday Times Golden Globe Race, a single-handed, round-the-world yacht race held in 1968-69. Soon after starting the race his boat, the Teignmouth Electron, began taking on water.

Donald Crowhurst: The fake round-the-world sailing story behind The Mercy. The mysterious and tragic disappearance of the single-handed sailor Donald Crowhurst more than 50 years ago continues to ...

Donald Crowhurst was born in British-controlled India, where his father worked on the railways, in 1932. Crowhurst spent his childhood there before returning to the family's native Britain soon after India gained independence in 1947. ... Adventurer and millionaire Francis Chichester had just sailed his yacht, the Gipsy Moth, around the world ...

07 Feb 2018. The Mercy starring Colin Firth portrays Donald Crowhurst's tragic attempt to sail around the world single-handedly in the first race of its kind. Maritime specialist Jeremy Michell sheds light on the perils of sailing alone, the progress of yacht racing, and the importance of remembering failure. By Kate Wilkinson.

When the yachtsman Donald Crowhurst set out from Teignmouth, Devon, on October 31, 1968, as the last of nine competitors to enter the Sunday Times Golden Globe race for solo, non-stop ...

Which is why Crowhurst's life, and death, have so fascinated writers and filmmakers ever since he plunged over the side of his small trimaran during the first nonstop, round-the world yacht race ...

Donald Crowhurst on his boat, ... And then there was Donald Crowhurst, amateur yachtsman and father of four, owner of a floundering marine electronics business who yearned for bigger things.

The compelling story of the fateful voyage of Donald Crowhurst, an amateur yachtsman who entered the most daring nautical challenge ever — the very first solo, non-stop, round-the-world boat race.

Drama on the waves: The Life And Death of Donald Crowhurst In 1968 an amateur sailor set off on the inaugural solo round-the-world yacht race. Incredibly, he appeared to be leading the race until ...

Donald Crowhurst, a father of four with a dream and a rickety sailing boat, disappeared during the 1968 Golden Globe race. His tale has inspired two movies, including Hollywood blockbuster "The ...

Directed by Simon Rumley, 2017. Studiocanal. When British businessman Donald Crowhurst set off in October 1968 to take part in a single-handed round-the-world boat race, he probably thought his ...

In 1968, British newspaper The Sunday Times sponsored the first ever round-the-world yacht race. Guaranteed excellent publicity from the paper, nine contestants enlisted, drawn by the glamor of winning such a race, as well as the £5,000 prize for the fastest time (as much as $120,000 today). ... Donald Crowhurst was not a professional sailor ...

Futility Closet 9:17 am Thu Jul 21, 2016. In 1968 British engineer Donald Crowhurst entered a round-the-world yacht race, hoping to use the prize money to save his failing electronics business ...

The Mercy: Directed by James Marsh. With Colin Firth, Eleanor Stagg, Rachel Weisz, Zara Prassinot. The incredible story of amateur sailor Donald Crowhurst and his solo attempt to circumnavigate the globe. The struggles he confronted on the journey while his family awaited his return is one of the most enduring mysteries of recent times.