My Cruiser Life Magazine

Cutter Rigged Sailboats [GUIDE] Advantages, Sailing, Options & Features

Cutter rigs are often more prevalent in boating magazines and theory than they are in your marina. Most cruising sailboats are Bermuda rigged sloops with just one permanently attached headsail. So, are two headsails better than one? Or, are they double the trouble?

Table of Contents

- History of Cutters

What is a Cutter Rig?

Cutter features, cutter rig options, sailing a cutter rigged sailboat, 5 popular manufacturers making cutter rigs, it takes two to tango, cutter rigged sailboat faqs.

History of Cutters

Cutters became popular in the early 18th century. These traditional cutters were decked (instead of open) and featured multiple headsails. Smugglers used cutters to smuggle goods, and the coast guard used cutters to try to catch the smugglers.

Various navies also used the cutter rig. Navy cutters featured excellent maneuverability and were better at sailing to windward than square-rigged ships.

Navies used cutters for coastal patrol, collecting customs duties, and “cutting out” raids. These “cutting out” operations consisted of a boarding attack. Fast, maneuverable cutters could stealthily approach an enemy vessel and board it. This type of attack was common in the late 18th century.

US Coast Guard ships, now powerful, fast, engine-driven, steel vessels, are still called cutters today as a nod to their past.

A cutter rig sailboat has two headsails instead of just one. The jib is located forward and is either attached to a bowsprit or the bow. The inner sail is called the staysail and is attached to an inner forestay.

Traditional cutters were built for speed. Today, cutter rigged sailboats are popular with ocean-crossing sailors, cruisers, and sailors looking for an easy to manage, versatile rig for all conditions.

It’s important to distinguish cutters from other types of boats with a single mast. Cutters regularly fly two headsails on nearly every point of sail. Many sloops are equipped to fly different-sized headsails, but it is unusual or unnecessary for them to fly more than one at a time.

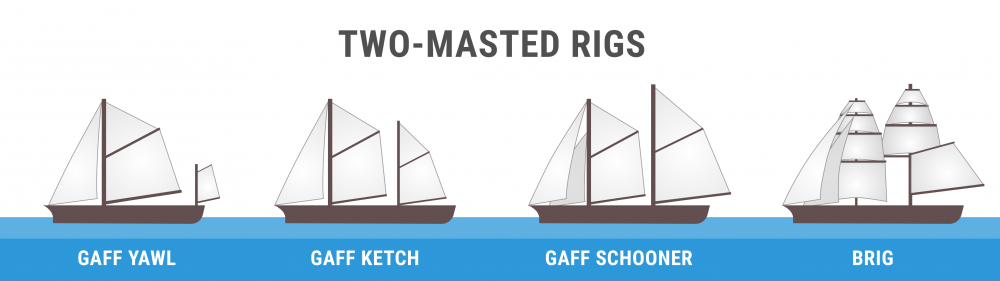

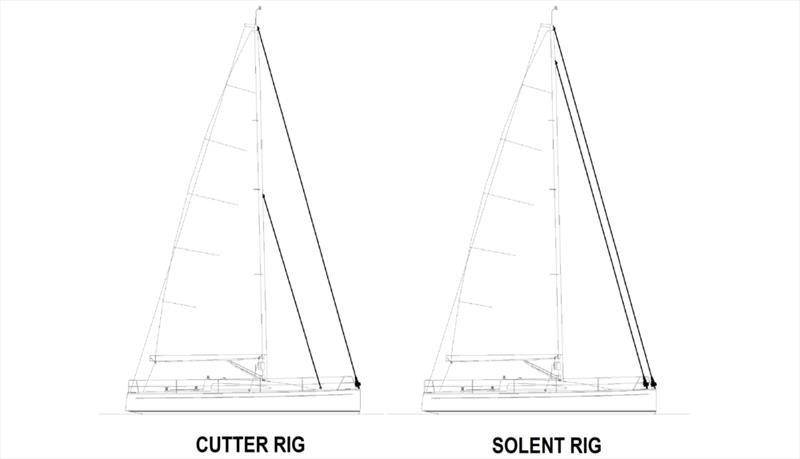

Solent Rig vs Cutter Rig

A solent rig is traditionally called a slutter–a little bit sloop and a little bit cutter. This configuration features two large headsails mounted close together. The solent rig is good if you do a lot of downwind sailing. You can pole out both headsails and go wing-on-wing, with one headsail on the starboard side and one on the port side.

If you are on any other point of sail, you can only use one solent rig headsail at a time. If you use the inner sail, the wind flow is disrupted by the furled forward sail. And, if you use the forward sail, you’ll have to furl it to tack because there’s not enough space between the forestays.

The solent rig is a way to add more sail options to a standard sloop. Most solent stays are not required rigging to keep the mast up, so owners remove them when not in use to make tacking the primary headsail easier.

Advantages of a Cutter Rig

There are a lot of reasons to like a cutter. A cutter rigged boat has redundant rigging and spreads the sail load across its rigging. And a cutter rig offers increased sail options–it offers increased sail area in light winds and easy and efficient ways to decrease sail area in heavy weather.

In heavy weather, a cutter will drop or furl her larger headsail – usually a yankee or a genoa. That leaves just the smaller inner staysail. This arrangement is superior to the standard sloop, which sails in high winds by reefing her headsail. The staysail, however, lowers the center of effort on the sail plan and maintains draft over the reefed mainsail. That makes the boat more stable, maintains performance, and reduces stresses on the rig.

If you imagine the sailor going to sea and needing to reef, it’s easy to see how many more choices they have than the sloop sailor. While each sailor can reef their mainsail, a cutter skipper has full control over both headsails as well.

Because a cutter rig spreads the load across two headsails, it’s easier to manage. There might be more sails, but each sail is smaller and has smaller loads on it. That makes cutters the preferred option for sailing offshore when short-handed, as are more cruising couples.

Lastly, it has to be added that there’s something appealing about the traditional looks of a cutter.

Disadvantages of a Cutter Rig

While there are many benefits of a cutter, there are drawbacks and disadvantages too.

Sailors will have more lines to manage and more processes to think through. More sails mean more halyards and sheets. And when it comes to maintenance and upkeep, a cutter will have more standing and running rigging to replace, along with one more sail.

Cutters are also harder to tack. You’ll be dealing with two headsails instead of just one. Many designs deal with this problem by making the staysail self-tacking. This has fallen out of favor, but it’s a great advantage if you find yourself short-tacking up or down rivers.

Regardless of whether you need to tack both headsails or not, getting the larger sail to tack through the slot and around the inner forestay is sometimes a challenge. Many skippers find themselves furling the headsail, at least partially, to complete the tack.

Cutters need extra foretriangle room, which can mean adding a bowsprit, moving the mast back, or both.

Cutter Rig Position

Looking at a cutter rigged sailboat diagram, you might see a bowsprit depicted. Often, cutters fly their yankee from a bowsprit. Bowsprits allow boat designers to increase the fore triangle’s size without making the mast taller. Other cutters don’t use a bowsprit and mount the yankee sail on the bow.

A cutter sailboat might seem like more work. After all, there are two sails to trim and manage. In addition, you’ll have to perform maintenance on two sails and purchase and maintain double the hardware.

However, the two headsail arrangement can be easier to manage when the sails are under load. Instead of having one jib or genoa to trim, the weight and pressure are spread across two sails.

Mast Location

Today’s modern boat designers often focus on providing living space in the cabin. Designers often move the mast forward to create a larger, more open saloon. When the mast is forward, there’s less space to mount two headsails. A cutter sailboat needs a decent foretriangle area.

A cutter rigged sailboat is also more expensive for boat builders. The deck must be strong enough to handle the inner forestay’s loads. Between the additional building costs, saloon design issues, and customers’ concern over increased complexity, boat builders often favor a single headsail.

Easier on the Boat and Crew

Since the loads are distributed between two smaller sails instead of being handled by one large genoa. This means there’s less pressure on attachments points and hardware, and therefore less wear and tear. In addition, because there are separate attachment points on the deck for each sail, the load is distributed across the deck instead of focused on one spot.

Because each headsail is smaller, the sails are easier to winch in, so the crew will find it easier to manage the sails.

There’s nothing cookie-cutter about a sailing cutter. From the cut of the jib to the configuration of the staysail, each cutter sailboat is unique.

Yankee, Jib, or Genoa

Traditional cutters have a yankee cut headsail along with a staysail. The yankee is high-cut and usually has no overlap. The high cut improves visibility, and a yankee has less twist than a typical jib. By sloop standards, it looks very small, but on a cutter it works in unison with the staysail.

A jib is a regular headsail that does not overlap the mast, while a genoa is a big jib that does overlaps. The amount of overlap is measured in percentage, so a 100-percent working jib fills the foretriangle perfectly. Other options include the 135 and 155-percent genoas, which are popular for sailors in light winds.

The problem with using a big jib or genoa with a staysail is that there will often be a close overlap between the two headsails. If flown together, the air over the staysail interferes with the air over the outer sail, making each one slightly less efficient. In these cases, it’s often better to drop the staysail and leave it for when the wind pipes up.

Roller Furler, Club, or Hank-On Sails

Sailors have many options to manage and store their cutter’s sails. Sailors can mix and match the options that work for them.

Roller Furler vs Hank-on Sails

You can have both sails on roller furlers, both hanked on, or a mix of the two.

Buying and maintaining two roller furlers is expensive, but it makes the sails easy to manage. You can easily unfurl, reef, and furl both headsails from the cockpit without having to work on the deck.

Hank-on sails are fool-proof and offer less expense and maintenance. You can use a hank-on staysail, either loose-footed or club-footed, depending on your needs. Hank-on sails make sail changes easy and they never jam or come unfurled unexpectedly.

The most common setup on most cutters is to have the larger yankee or jib on a furler, and the smaller and more manageable staysail hanked on.

Club-footed Staysail

A club-footed staysail is attached to a self-tacking boom. Since there is only one control sheet to handle, there’s a lot less work to do to tack from the cockpit. It tacks just like another mainsail. You can tack the yankee while the club-footed staysail self-tacks.

Island Packets and many other cutters feature this arrangement, which makes tacking easy.

However, a club-footed staysail takes up space on the foredeck–it’s always in the way. It’s harder to get to your windlass and ground tackle. In addition, it’s harder to store your dinghy on the foredeck under the staysail boom. The boom also presents a risk to anyone on the foredeck, since it can swing during tacks and jibes and is even lower to the deck than the mainsail boom.

Loose-footed Staysail

Keeping a loose-footed staysail on a furler clears space on the deck. Without the boom, you can more easily move around the foredeck, and you’ll have more space when you are managing the anchor. In addition, you can more easily store your dinghy on the foredeck.

However, the staysail loses its self-tacking ability. You’ll now have to have staysail tracks for the sheet’s turning blocks and another set of sheet winches in the cockpit. When it comes time to tack the boat, you’ll have two headsails with four sheets and four winches to handle. Most owners choose to furl the outer headsail before the tack. Then, they can perform the maneuver using the staysail alone.

The good news is that most offshore boats are not tacking very often. If you’re on a multi-day passage, chances are you’ll only tack once or twice on the whole trip.

Downwind and Light Air Sails

There are a number of light air sails that will help your cutter perform better when the wind is light. Popular options include the code zero, gennaker, and asymmetrical spinnaker.

Adding one of these sails to your inventory can make it a dream sailing machine. A code zero can be flown in light air. Since the cutter is already well equipped for sailing in heavy air, a light air sail really gives you the ability to tackle anything.

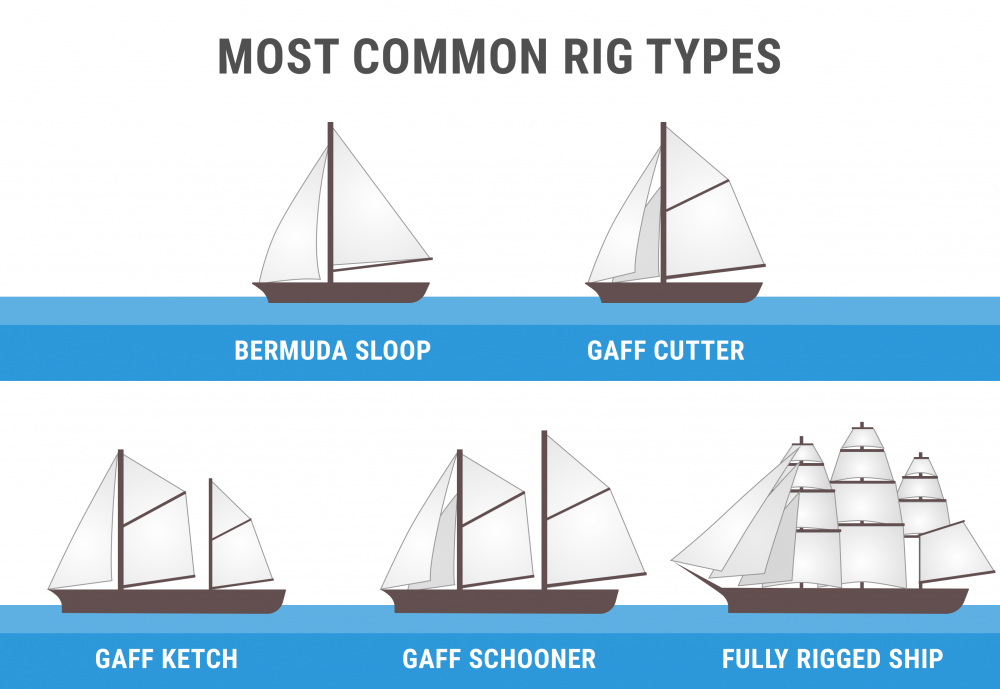

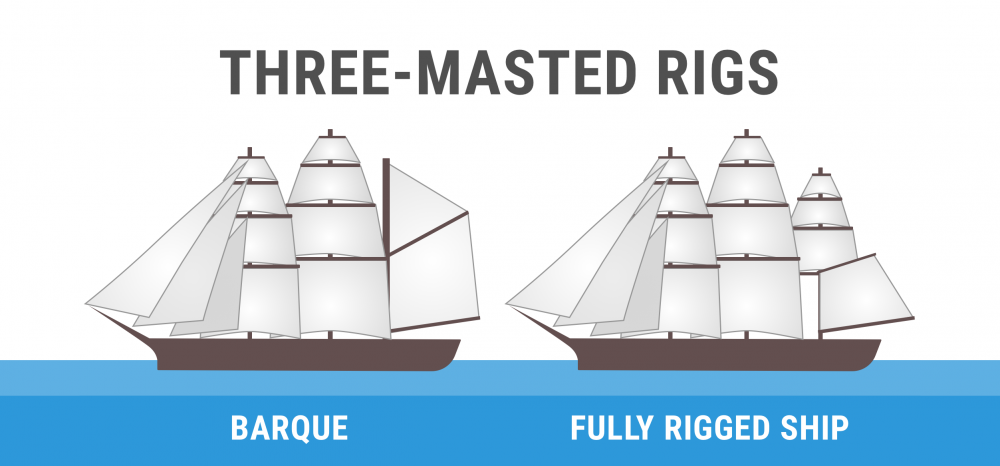

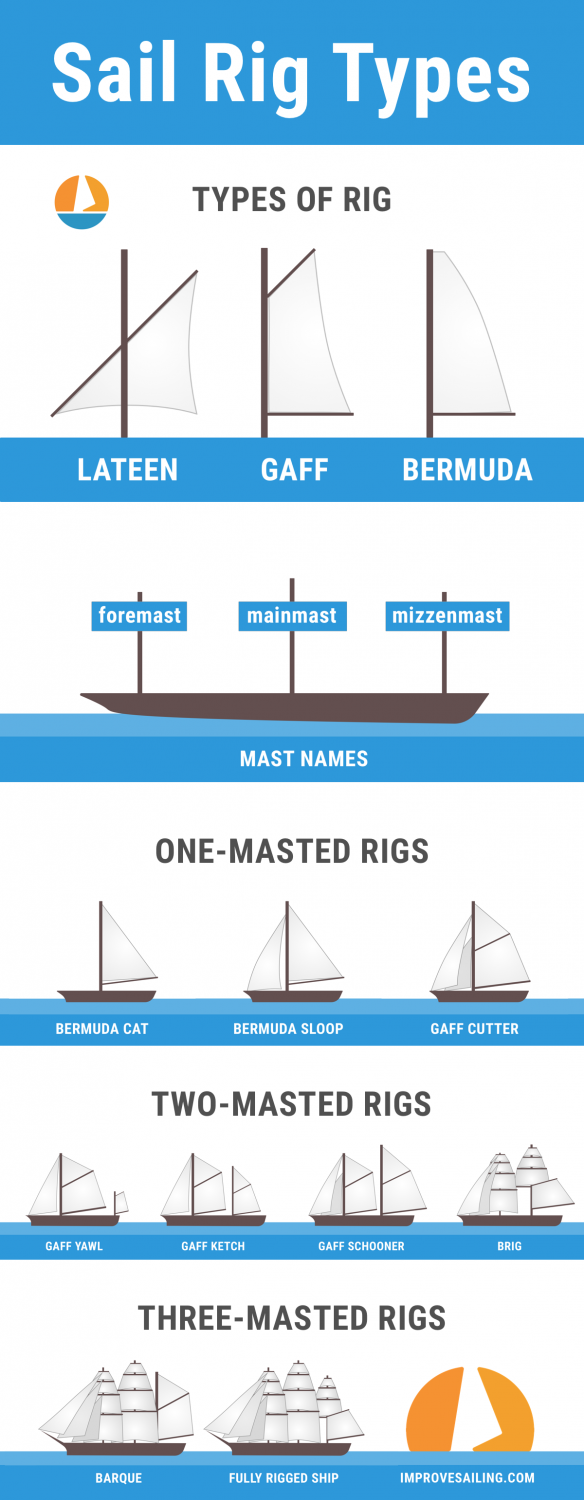

Sloop Rig, Ketch, and Yawl

While some describe a cutter as a cutter-rigged sloop or a sloop cutter, a modern sloop has one mast and one permanent headsail.

But you’ll also find the cutter rig used on a ketch or a yawl. A cutter ketch or yawl offers a cruising sailor increased sail area and choices by adding the mizzen mast and sail behind.

Sailing a cutter rigged boat is not that different from sailing a traditional sloop. Sailors will have to pay close attention to trim and tacking.

Sailing a Cutter Rig to Windward

A cutter usually can’t point as high as a sloop when sailing to windward. The yankee hinders the staysail’s airflow, and the staysail starts to stall.

Tacking a Sailboat Cutter

If you need to short tack up a narrow channel, and both your sails are loose-footed, you can roll up one of the headsails and just use one headsail to tack. Many staysails have a boom and are self-tacking. This means you can tack the yankee, and the staysail will take care of itself.

Reefing a Cutter

A cutter sailboat has more options to easily get the right amount of sail. You can add a reef to your mainsail, then furl or reef the yankee a little, and then add another reef to the mainsail. As the wind increases, you can take the yankee in all together, and sail with a double-reefed mainsail and the staysail. Finally, you can add the third reef to the mainsail. Some staysails can be reefed, too.

A cutter rig offers many options during heavy weather. For example, you may end up taking the mainsail down altogether and leaving the staysail up. Or, you might choose to replace the staysail with a tiny storm sail.

Adding a storm jib on a sail cutter is much easier than a standard sloop. On a sloop, you’d have to remove the large genoa from the bow and then add the storm sail. This operation places the skipper in a challenging situation, which can be avoided on a cutter.

On a cutter, you can remove the staysail and add the storm jib to the inner forestay. Working a little aft of the bow will give you increased stability while managing the staysail’s smaller load.

While many modern sailboats are sloop-rigged, cutter-seeking sailors still have options.

Rustler Yachts

While many new yachts have ditched the sturdy offshore cutter rig in favor of greater simplicity, Rustler is making a name for themselves by bringing it back. It’s still one of the best options for offshore sailing, and it’s great to see a modern yacht company using the rig to its full potential.

The Rustler doesn’t need a bowsprit to accommodate its cutter rig. The Rustler is set up for single-handed and offshore cruising with all lines managed from the cockpit. Their smaller boats are rigged as easier-to-sail sloops for coastal hops, while the larger 42, 44, and 57 are rigged as true cutters with staysails and yankees.

Cabo Rico Cutters

Cabo Rico built cutters between 34 and 56 feet long. They aren’t currently in production but often come up on the used boat market. They are beautiful, semi-custom yachts that turn heads where ever they go. Of all the cutters the company built, the William Crealock-designed Cabo Rico 38 was the most long-lived, with about 200 hulls built. The second most popular design was the 34. The company also built a 42, 45, 47, and 56—but only a handful of each of these custom beauties ever left the factory. Most of the larger Cabo Ricos were designed by Chuck Paine.

Cabo Ricos have bowsprits, and the staysail is usually club-footed, although owners may have modified this. Cabo Ricos are known for their solid construction, beautiful teak interiors, and offshore capabilities.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Hold Fast Sailing (@sparrowsailing)

Pacific Seacraft

Pacific Seacraft features a full line of cutters. Pacific Seacraft boats are known for their construction, durability, and overall quality.

Just a few of the best-known cutters built by Pacific Seacraft include the following.

- Pacific Seacraft/Crealock 34

- Pacific Seacraft/Crealock 37

- Pacific Seacraft 40

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Jeffersön Asbury (@skipper.jeff)

Island Packet Yachts

Island Packet boats are probably the most popular cutter design available today. Designer and company founder Bob Johnson created beautiful cutter-rigged full-keel boats with shallow drafts that were very popular around Florida, the Bahamas, and the east coast of the US.

Island Packets are known for their comfortable, spacious layouts. Older models could be ordered from the factory as either sloop or cutter-rigged. The result is that you see a mix of the two, as well as plenty of cutters that have removed their staysails to make a quasi-sloop.

Island Packet is still in business today, but now favors solent-rigged sloops with twin headsails.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by SV Miette (@sv_miette)

Hess-Designed Cutters

Lyle Hess designed several famous cutter-rigged boats, including the Falmouth Cutter 22 and the Bristol Channel Cutter 28. These gorgeous boats are smaller than most cruising boats but are a joy to sail. Lyle Hess’ designs were popularized by sailing legends Lin and Larry Pardey, who sailed their small wood-built cutters Serraffyn and Taleisin around the world multiple times.

These beautiful cutters have a timeless look like no other boats. They have inspired many other designs, too. You’ll find them built from both wood or fiberglass, but a variety of builders and yards have made them over the years.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Professional photographer (@gary.felton)

Cutter rigged boats offer cruising sailors a flexible sail plan that’s perfect for offshore sailing. Sailors can adjust the amount of sail according to the current wind conditions. Traditional cutters were known for being fast and agile, and today’s cutters carry on the tradition with pride.

What is a cutter rigged yacht?

A cutter rigged yacht features two headsails. One headsail, usually a high-cut yankee, is all the way forward, either on a bowsprit or the bow. The staysail is smaller and attached to an inner forestay.

What is the advantage of a cutter rig?

A cutter rig offers cruising sailors more flexibility. They can easily increase and decrease the sail area and choose the optimum combination for the sailing conditions. While there are more lines and sails to handle, each sail is smaller and therefore easier to manage.

Matt has been boating around Florida for over 25 years in everything from small powerboats to large cruising catamarans. He currently lives aboard a 38-foot Cabo Rico sailboat with his wife Lucy and adventure dog Chelsea. Together, they cruise between winters in The Bahamas and summers in the Chesapeake Bay.

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Find A School

- Certifications

- North U Sail Trim

- Inside Sailing with Peter Isler

- Docking Made Easy

- Study Quizzes

- Bite-sized Lessons

- Fun Quizzes

- Sailing Challenge

What’s in a Rig? The Cutter Rig

By: Pat Reynolds Sailboat Rigs , Sailboats

What’s in a Rig Series #2

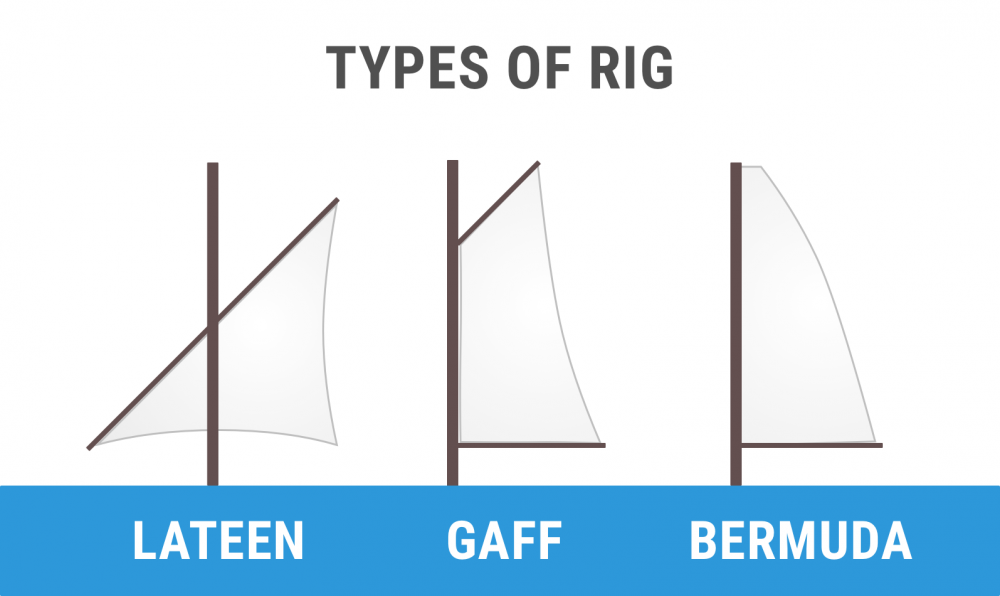

A variation on the last installment of What’s in a Rig (the sloop) is the Cutter Rig. Although it has gone through some changes through the course of history, the modern cutter rig is generally a set-up with two headsails. The forward sail is called the yankee and the one slightly behind it is the staysail.

Cutter rigs are a choice a cruising sailor might opt for more offshore work. Since longer passages usually means encountering heavier weather, the cutter rig can be the perfect choice to have a ready-to-go balanced sailplan when the wind picks up. They are not quite as easy to tack as sloops, but since cruisers go for days without tacking, the ability to quickly furl the yankee and have a small staysail up in a stiff breeze is worth the sacrifice.

Cutter rig fans also enjoy the balance it provides. A small staysail set farther back on the boat and a reefed main is a very solid arrangement on a windy day and for cruisers who want to be comfortable in 25-knots, this is important. Also, a staysail makes heaving-to easier – this is a task far more utilized by the cruising sailor.

So, there you have it – the cutter rig is a set-up preferred by sailors on a voyage. They have disadvantages in how they tack but strengths in how they behave in open-ocean conditions.

What's in a Rig Series:

Related Posts:

- Learn To Sail

- Mobile Apps

- Online Courses

- Upcoming Courses

- Sailor Resources

- ASA Log Book

- Bite Sized Lessons

- Knots Made Easy

- Catamaran Challenge

- Sailing Vacations

- Sailing Cruises

- Charter Resources

- International Proficiency Certificate

- Find A Charter

- All Articles

- Sailing Tips

- Sailing Terms

- Destinations

- Environmental

- Initiatives

- Instructor Resources

- Become An Instructor

- Become An ASA School

- Member / Instructor Login

- Affiliate Login

Attainable Adventure Cruising

The Offshore Voyaging Reference Site

- Cutter Rig—Optimizing and/or Converting

In the last two chapters I covered why a true cutter is a great rig for short-handed offshore voyaging and how to decide if the cutter rig is right for you .

Now I’m going to cover what it takes to successfully convert a sloop or even a ketch to get most, or maybe even all, of the benefits that we true cutter owners are so damned smug about.

Also, if you have a cutter, but are less than happy with her, read on. Making a cutter rig work really well, like so many things in offshore voyaging, requires getting the details right, and that’s what this chapter is all about.

Login to continue reading (scroll down)

Please Share a Link:

More Articles From Online Book: Sail Handling and Rigging Made Easy:

- Six Reasons To Leave The Cockpit Often

- Don’t Forget About The Sails

- Your Mainsail Is Your Friend

- Hoisting the Mainsail Made Easy—Simplicity in Action

- Reefs: How Many and How Deep

- Reefing Made Easy

- Reefing From The Cockpit 2.0—Thinking Things Through

- Reefing Questions and Answers

- A Dangerous Myth about Reefing

- Mainsail Handling Made Easy with Lazyjacks

- Topping Lift Tips and a Hack

- 12 Reasons The Cutter Is A Great Offshore Voyaging Rig

- Cutter Rig—Should You Buy or Convert?

- Cruising Rigs—Sloop, Cutter, or Solent?

- Sailboat Deck Layouts

- The Case For Roller-Furling Headsails

- The Case For Hank On Headsails

- UV Protection For Roller Furling Sails

- In-Mast, In-Boom, or Slab Reefing—Convenience and Reliability

- In-Mast, In-Boom, or Slab Reefing —Performance, Cost and Safety

- Making Life Easier—Roller Reefing/Furling

- Making Life Easier—Storm Jib

- Swept-Back Spreaders—We Just Don’t Get It!

- Q&A: Staysail Stay: Roller Furling And Fixed Vs Hanks And Removable

- Rigid Vangs

- Building A Safe Boom Preventer, Part 1—Forces and Angles

- Downwind Sailing, Tips and Tricks

- Downwind Sailing—Poling Out The Jib

- Setting and Striking a Spinnaker Made Easy and Safe

- Ten Tips To Fix Weather Helm

- Running Rigging Recommendations—Part 1

- Running Rigging Recommendations—Part 2

- Two Dangerous Rigging Mistakes

- Rig Tuning, Part 1—Preparation

- Rig Tuning, Part 2—Understanding Rake and Bend

- Rig Tuning, Part 3—6 Steps to a Great Tune

- Rig Tuning, Part 4—Mast Blocking, Stay Tension, and Spreaders

- Rig Tuning, Part 5—Sailing Tune

- 12 Great Rigging Hacks

- 9 Tips To Make Unstepping a Sailboat Mast Easier

- Cruising Sailboat Spar Inspection

- Cruising Sailboat Standing Rigging Inspection

- Cruising Sailboat Running Rigging Inspection

- Cruising Sailboat Rig Wiring and Lighting Inspection

- Cruising Sailboat Roller Furler and Track Inspection

- Download Cruising Sailboat Rig Checklist

Thanks John, that’s a lot of thought and education for me with my old wooden cutter. Up to now I’ve been thinking of the staysail and the running backstays as generally more of an impediment than a help, especially when single handed, but you’ve made me realise I should be paying more attention to them, and maybe even start using the winches! Keep up the good work.

Thank you, John. Gratitude is a Brewer 44 ketch. She is rigged with a baby stay and tracks that look (from the pictures) like they are well placed. We have dual winches on each side and have a staysail, which we (sorry to admit) have never flown because, when we are offshore, the dinghy is on the foredeck and there is so much stuff up forward. Do you have any experience running a Brewer as a “cutter”? Ted Brewer insists it not be called a cutter ketch, but rather an ketch rig with a double foresail plan. Any thoughts and recommendations would be welcome as, when we are offshore, there usually is enough time to tinker with a rig!

No I have not sailed a Brewer 44, but I know the boat and would expect her to do just fine with a cutter rig, once you get it set up right, as above.

Hi John, Great article, I love my cutter, and find that my boat points at least 5 degrees higher when sailed as a cutter, rather than as a sloop.( I have a removable inner forestay with a Highfield lever for tensioning it) . I have a hanked on staysail , which I prefer on smaller cutter, say under 40 ft. This allows one to have a hanked on storm jib, if things get seriously windy. I appreciate the need for a furling staysail on larger boats, but would always prefer a hanked on storm jib. I have been thinking about replacing my 1x 19 SS running backstays with Spectra or Dyneema. I have not seen any cutters yet that have done so, but there could be a lot of advantages. Any thoughts on that?

We replaced out wire runners with high tech rope some 10 years ago and would never go back to wire. You can see ours in the picks above.

The big advantage is that being lighter they don’t slap around and therefore don’t try to jump out of our hands as we run them forward.

I’ll mention the old fashioned boomed staysail again here since it can eliminate the sheeting track issue and also offers other advantages.

We have a wishbone boomed staysail that sheets to a fixed point. We use twings that lead aft through blocks attached at the inner shroud chainplates for fine adjustments when the wind is forward of the beam and use a preventer when it’s further aft.

The twings don’t need winchs since we can ease the sheet slightly, adjust the twing to its pre-marked position and harden in the sheet again. Excellent sail control on all points of wind.

Like any other system there are disadvantages but it really works well for us and is another option worth considering.

Hi Pat I’m attracted to the wishbone boom as it makes self-tacking elegantly simple and does away with a lot of deck gear. It limits the area to non-overlapping, but that I would easily accept on a staysail. My main concern is how to carry the loads from the forward end of the wishbone boom. Is yours attached to the stay? Wouldn’t that push the stay forwards at that spot, causing deformation of the sail? Or has the sail been shaped with that in mind? Or have you got some other smart system I haven’t yet thought of?

Hi Stein The forward end of our wishbone connects to a SS tube that slides up the 7×7 wire rope stay. It is slightly bowed, has flared ends and a plastic inner sleeve that extends above and below to better distribute the distortion of the stay.

Yes, our sail is cut to allow for the distortion of the stay but I’ve seen a number of wishbone staysails where the piston hanks were simply attached with different lengths of lashing to allow for this.

Hi Pat That attachment method seems good. I think the wear on the wire will be no more than it is at the exits of the terminals, so it will most likely not reduce the working life of the wire. But I still have some questions. 🙂

A sail shaped for the bend in the stay or adjusted at the hanks, will of course be just as well shaped as with any other configuration, but how is the behaviour with different loads and trim tensions on the sail? If you tension the boom outhaul (if that’s the correct English term?) it will increase the push on the stay. Will that make the sail shape uneven so you have to tension the stay, or am I wrong?

Also, I assume you don’t reef the staysail, but keep it either full or take it down? If you reef it, I guess the boom must come down with the sail? Do you know of methods to facilitate reefing?

Hi Stein I haven’t noticed any significant distortion of the luff area due to thrust of the wishbone on the forestay when adjusting outhaul tension. I must admit I am not a fanatic sail trim person but the sail always looks OK. I don’t reef my staysail (I’ve never had to) but can see no reason why not and may well put reefing points on the next one. The bottom portion would remain in place and you would reef the luff and leech down to the boom.

I have to confess that I’m a jib boom hater, part of my fixation on clear decks . Having said that, I agree that there are benefits, but to me they are outweighed by the disadvantages. I suspect that in the final analysis, despite my prejudices, it all comes down to personal preference.

Hi John I understand your dislike of clutter but have found that when it’s not in use the wishbone is a useful handhold amidships when moving about on the foredeck . When it’s in use it’s no more ‘in the way’ than the sail itself.

Hi John. Another good post, as always.

I’ll just give a comment on the polyester vs epoxy topic, and health issues. There is no doubt that epoxy is a better material. Tolerates higher compressive loads, is stiffer but still stretches more without cracking, adheres better, impregnates the fibres better, is watertight (polyester is as watertight as a very dense sponge) and more.

Of course I prefer epoxy, but still there are potential problems. One should be careful with relatively fresh polyester. Even up to a couple of years old, it may in some cases contain enough styrene to damage the epoxy. The styrene evaporation is what gives the stench when polyester hardens, and the characteristic “plastic” smell in new boats. In sufficient amounts, it will soften the epoxy structure permanently.

Most epoxies will cure fine in room temperature with no added pressure and mechanical properties clearly better than any polyester. Still, if cured under pressure (like vacuum bagging) and high temperature (preferably at least 50 degrees C / 120 F) the strength will normally double or triple. Applying those conditions are normally close to impossible in an existing boat. As mentioned, epoxy is still better than polyester, but many boat builders will relate to how it “should be done” and then advice for polyester. They can be honest and even not lazy, just “emotional”. 🙂 Polyester also hardens faster, so the work process is faster, thus cheaper. With epoxy, you frequently have to wait overnight or more.

For self-builders, there is another big problem with epoxy: It’s an extremely strong allergen. Polyester smells really bad, so it’s easy to notice that one should not inhale the fumes but use ventilation and protective gear. Most epoxies make way less fumes and they don’t smell strong, even while curing. Still you need to be more careful. Epoxy fumes and uncured epoxy is serious stuff. If you get wet epoxy on your skin, nothing much happens, normally. It’s sticky but not too hard to wash off. Use water and soap. Alternatively the cleaning stuff used by car mechanics etc. NEVER use any solvent to clean your skin. It will penetrate your skin and bring both solvent and epoxy into your blood. It’s like drinking it!

If you’re sensitive or are repeatedly exposed to epoxy, you will sooner or later get serious skin rashes or blisters. This is an allergic reaction, which epoxy provokes very efficiently. The trouble is that when you had that reaction once, you’re permanently allergic to epoxy, and frequently you will trigger other allergies too. I’ve managed to escape this, by being totally “nazi” with cleanliness and protection, but many of my sailing friends have serious problems with allergies from epoxy exposure. They do have continuous problems with it and wish they had been more careful.

One common bad thing to do is sand hardened epoxy and inhale some of the dust. At “room temperature” 23 degrees Centigrade, 73 Fahrenheit, almost all epoxies will need more than a week to cure fully. The “fast cure” ones too. The epoxy will harden much sooner, but a full cure takes time unless the temperature is significantly higher. Also, a complete cure depends on a thorough mixing of the resin and hardener. If you breathe in not fully cured epoxy dust, you get chemically active particles in your lungs. Not good. After a full cure, it’s way less harmful.

I’m not trying to say that you should avoid epoxy, but I can’t overemphasise this: You are dealing with a chemical reaction that is a really bad match for your body. Being relaxed about it is not smart. To make things worse, being totally clean when working with epoxy is hard. You need to establish methods that work for you and your specific task. If you work inside a boat, I’d use a hose to extract air from further inside the boat than where you are working. That way there will be a continuous flow of air across the work area and away from you. A vacuum cleaner is good enough. Placed it outside the boat, away from where fresh air flows in, with a long hose. Preferably remove the dust collecting bag etc, to increase flow.

You need to use gloves, of course. I normally use “surgical gloves”, those you can buy in most pharmacies. Latex is useless, as epoxy will penetrate them quickly. Vinyl is clearly better, but will also be penetrated. The by far best is “Nitrile rubber”. If you wear thin cotton gloves inside, it will increase the duration of the gloves. Sweaty hands will speed up penetration. Either way, change cloves frequently, depending on how much exposure, but at least every 10 minutes if you get epoxy on them. Use a blocking cream on your hands and lower arms. Use clothes you can dispose of or clean efficiently. Make sure you breathe fresh air. In some situations, a full face mask is smart, those plastic sheets that just cover. Cheap stuff. Make sure you can work without stress. Stress will make you cut corners. Then you will be exposed.

If you take proper care, epoxy is an amazing material and building stuff is great fun! Good luck!

Lot’s of good information, thank you. One of the reasons I recommended the west system products and manuals is that they do a really good job of explaining the safety precautions that we must take when using epoxy.

Also, west even have a manual on how to use vacuum bags.

One thing, I think I’m right in saying that temperature and speed of cure don’t have any measurable effect on strength, at least of West epoxy.

And even if they do, for the applications we are talking about, I don’t think it matters much. On the boats we are dealing with here, if there is any doubt at all, just up the strength of the upgrade or repair.

Bottom line, I fixed an old racing boat with really bad structural issues with the west system and found it all pretty easy and very forgiving to use. And at the end of the project the boat was far, far stronger than she was when new.

Hi John You are completely right on what cure methods mean for this type of use. Epoxy is a structurally very good material no matter how it’s cured. The reason for using higher temps and pressure is not that it’s necessary but that it’s possible and gives improvements. These improvements are important when the epoxy is used like with carbon in a mast, where its physical properties need to be fully exploited.

All epoxies, also West, change their properties with higher temp cures. The data sheets for professional users show this. It’s a property of the base resin. It gets harder and at the same time tolerates more compression and stretch. The purer the epoxy is, the stronger this effect is. The main reason for mentioning it was that it might be why pro users are hesitant to using epoxy in areas they can’t get the max strength out of it. That reason is irrelevant, though. Just a bad excuse to avoid a more work intensive material.

The West Epoxy is primarily aimed at amateurs, so they are good at adapting to that. Lots of good info. I would also recommend their products. Another producer that has some of that focus, but not quite as good on the info, is SP Systems. They also work some with the high-end pros, have a larger spectrum of products and own some of the factories themselves.

Both of these are definitely high on price though. Buying from other sources via industrial channels may lower prices to less than a fourth, or much more, but normally means you need to buy it in barrels and the level of service, users equipment and info is as much lower as the price. You’re expected to know more than the provider. For the use we are talking about here, this is normally a bad solution and West etc will be better even on price, as you can buy small quantities.

Hi John, Yes, that is a problem I have with my SS runners. My method of securing them in the stowed, unused, position, entails passing a hook with a wire strop through the lower eye, and then tensioning them aft ,with a small tackle. It can be a bit of a struggle in rough seas. When you mention ” high tech” rope, what exactly are you using? I too, am totally against staysail booms, bloody dangerous things in my experience. The dangers far outweigh any self tacking benefits, especially offshore. I have a 6500nm delivery to N.Z. on a nice cutter later this month, looking forward to that.

Staysail boom haters unite! 🙂

Sorry, I’m not exactly sure which high tech rope we used. With these things I just tend to trust our rigger, but I can probably find out if it’s important. I’m pretty sure it was not Spectra because of the creep problems, and I know it was not PBO, because Jay doesn’t trust the stuff. I think it may be Technora.

Hi John, We sail a cutter formatted Hylas 47. Two up this sail plan is a dream. I was considering changing my runners to high tech line but am flummixed about how they would get attached up aloft. Currently the rigging wire versions are on T terminals, which fit into slots in the mast. I suppose there must be T terminal fittings that can attach to line but I have not managed to find any – maybe not looked hard enough? any thoughts / ideas would be welcome. Geoff

Hum, I don’t know, but I have to think that there must be a solution for this. Anyone else have any ideas?

I guess, in a worst case, you could have a rigger make up a short wire adapter from T terminal to an eye and then splice the high tech rope to the eye. Not very elegant, but should work.

I believe that you are looking for a “T ball bail”. There are a few different types that will show up if you google it but then you can splice directly to it or form a thimble through the bail.

Great article, and pertinent to my situation. I have a Whitby 42 (that you may know, BTW) that had the mizzen decommissioned. The two static aft stays, I believe, could act very much like running backstays. The removable inner forestay was replaced with a permanent unit (secured below as you mentioned), but does not stand parallel to the forestay/furler. I’m cognitive that this could cause issues with tacking/gybing, but wonder what other performance/trim issues this might present?

I guess it depends exactly where the top of the staysail stay terminates and how much off parallel the two stays are. If the answer is a lot, then I think that’s going to be a big performance hit and going with a true cutter rig might be a mistake.

Stein, Wonderful dissertation on safety and some of the characteristics of the adhesives. Bill, We use high tech rope for our runners and have been very happy with them. Stein, I would also argue against a wishbone rig for all the reasons mentioned. The staysail is just much to easy to tack: with good timing I hand snub most of it in and winch the last few inches, to warrant the extra gear and the danger of something hard flailing about the foredeck. My best, Dick Stevenson, s/v Alchemy

Hi Dick Thanks. 🙂 I agree that a staysail is very easy to tack, but it still takes one person to do it at the right moment. Sailing alone, that’s not always easy, so self-tacking has its value and I have used a lot of different systems that work ok, but not yet tried a wishbone boom, so finding someone with experience makes me curious. I mostly sail multihulls, like solo sailing and I’m a total speed addict, so I know my priorities are not the same as normal cruisers, but maybe still interesting to explore the possibility. Wishbone booms interest me for three reasons: 1. A track is the normal alternative for self-tacking, but clutter the decks badly, are ugly, expensive, vulnerable and unreliable. 2. The wishbone boom has no friction, so the sail will tack without trouble. 2. The sail will be perfectly shaped even at wider angles. Just let out the sail and it’s ready to work at another angle. No need for barber hauls and non-stop balancing of multiple ropes.

To me, it seems that a wishbone boom might give some big advantages that might be important enough to accept the disadvantage of having something moving around there. We either way accept that the main sail must have a boom that is a much bigger risk to us, as it’s mostly moving in the same area as our heads. 🙂

“The sail will be perfectly shaped even at wider angles. Just let out the sail and it’s ready to work at another angle. No need for barber hauls and non-stop balancing of multiple ropes.” This was what I hoped for but hasn’t been my experience and by the sounds of it you are much keener than me! I use haulers when close hauled to adjust leech tension and control sail twist and I usually use a preventer when off the wind. So, yes, there are lines to adjust but these can be done at your leisure after tacking.

Hi Pat I used to do racing as a profession, so I’m more keen on trim and details than most sailors. Meaning that I can be quite annoying when cruising. 🙂 But I still do enjoy cruising, as long as the boat works well and is used right. That’s why I’m interested in discussions here.

Preventers will naturally be useful, but I’d assume nothing else that needs attention after a tack…? An adjustable rope from the rear end of the wishbone boom, along the foot of the sail and attached to the base of the head stay, could keep the leech and twist as you want it.

Hi Stein Yes, I’m sure you would be maddening when cruising – constantly adjusting sail trim :).

Yes, a vang should theoretically keep the leech as wanted but will not control twist effectively. Sheeting from a central point limits control. I don’t find the barber haulers a problem since we are very rarely tacking repeatedly.

Just to clarify, tacking the way Dick and I do it, It doesn’t ” takes one person to do it at the right moment”. I tack our boat single handed all the time and the staysail just hangs out aback until I get around to dealing with it. No urgency or right moment at all.

For me the loss of easily reefing and furling the staysail is a complete killer of the wishbone boom idea. One of the coolest parts of the way we are set up is that we can quickly adjust the staysail size to get the boat the heave-to quietly in all conditions.

I think you may be better served with a self-tacking jib idea. Many production cruisers are now offering neat implementations ( have a look at Hanse for ideas) where the track is moulded onto the coach roof, with a narrow sheeting angle. The only compromise is the staysail/jib cannot overlap the mast which may reduce performance. I do not believe modern self-tackers clutter the decks since they do not come out beyond the line of the coach- roof.

We would have fitted a moulded track on our sloop and gone with a self-tracker, but we have no runners and instead a foreward “baby stay” to stop the mast inverting in extreme conditions, which prevents this. I’m with John on the jib boom idea.

Hi Rob Having sailed a Hanse sloop with a self tacking headsail I comment that it is not a good solution. It may be better for a staysail.

Interesting, this hasn’t been my experience in NZ Pat, but anyway – not my problem as we didn’t go down this track! Rob

Hi Rob I’ve tried a lot of different self-tacking systems. On small boats some of them work fairly ok if they are maintained well. On bigger boats, especially for long distance, I strongly doubt that it’s smart to have any of those. Those tracks are quite vulnerable. A bit of sand will destroy it quickly. Even the slightest disturbance will stop the automatic tacking. When you have to run on deck to kick them over, you don’t feel helped…

I’ve never tried a wishbone boom solution, apart from on windsurfers, but they are interesting in several ways. The most important advantage over tracks, apart from being much less vulnerable, is that it will let the sail keep its shape even at very wide angles with no barber hauls etc. The short tracks in the cabin top of some cruisers are only suitable for max upwind. That’s not frequently useful for cruising.

I’m a big fan of the cutter rig, but I’m also investigating alternative layouts, mostly suitable for fast catamarans, where overlapping sails are generally not too useful either way. That (and general curiosity) is my reason for being interested in details about wishbone solutions.

I agree the sheeting can be narrow narrow, and needs to be coupled with an off wind sail like a Code zero. In stronger winds (especially on a cat) I think the sheeting angle will be sufficient and the jib/ staysail being open in the head will not be a big issue. I raced on a 10m yacht class here in NZ with self-tacking jibs, and never had an issue. Why should jib tracks jam any more than mainsail tracks which nearly every yacht has?

The thought of a substantial jib boom sweeping our foredeck at knee height is much more worrying to me than any self-tacking jib issue. In the final analysis, we chose to keep things simple and opted for a conventionally rigged 100% jib. This tacks so quickly that a self-tracker / jib boom didn’t offer enough to warrant the cost/ added complexity.

Hi Rob Self tackers and wishbones are probably off topic, and I feel guilty for keeping this going on, but one more comment: I love simplicity almost as much as I love speed, 🙂 so I think a convensional sheet system on a cutter staysail is a good solution, probably the best in most cases. My interest in a wishbone boom is mostly connected to other rather uncenventional layouts, but Pat here likes his setup, so it must have some merit.

I’ve sailed racing multihulls with heavy duty mainsail tracks, longer than the LOA of some cruisers. Even those do jam slightly sometimes, but the consequences are normally minimal. The mainsail traveller only needs to move in gybes etc, when the sheet is looser, friction lower and the power pushing them out is always sufficient, as long as there is any wind. Upwind it stays in the centre. No movement.

A jib track needs to move under max tension, has much tighter angles and must move to the exact same spot every time. It gets less push the closer it is to the end stops and frequently rope tension increases at the same time. Good jib tracks with good control systems do do it perfectly, most of the time, but a trickier task means they fail way more often. A long distance cruiser can easily live with that, but I think the advantages are not worth the disadvantages. I think we agree on most of this topic. 🙂

Hi Rob The Hanse set up wasn’t bad with full sail and going to windward. With it partially furled or off the wind I found the sheeting point was far from ideal. Pat

my cutter experience is essentially nil hence this basic question re cutter tacking: I’m sure the stay sail tacks easily but not so with the Genny or the job top ? seems will need to furl this in enough to clear the inner stay then roll it back out once on the new tack ? pls pardon my ignorance on this…also do you know if matt has seen my question about sail drive prop efficiency I posted on his recent article re props ? would appreciate having his take on this when he can…cheers

richard in Tampa bay

Hi Richard,

No, it is not necessary to furl the jib top to tack. I described the procedure under #8 in this post .

We were out on another test sail yesterday and found even with a staysail stay relatively close to the forestay (about two feet or 60 cm.), it was fairly straightforward to tack (we haven’t done it for some time). To gybe is a different story, but the idea of letting the staysail back until the jib topsail is through (and in fact using the staysail as a sort of ramp to “help” the process) is quite practical. I explained “#8” to my wife and she grasped it immediately and wondered why a lot of people furl to tack. This pleased me. I also agree about staysail and main. Sure, you can’t point well, but it’s a lot more stately a progress if things are getting a touch hairy.

You may be interested in the sail plan of my boat: https://numawan.wordpress.com/2007/09/30/le-plan-de-voilure-the-sail-plan/#more-4

John … Great piece on cutter rigs – i’ve been following this closely after considering a conversion (currently have 135 Genoa and 10o Staysail, both on furlers) for a Hylas 49 … Been trying to solve several problems, boat tacks like a dog getting the 135 through the slot, frequently I’m short handed (my wife and I) and the 135 gets to be a handful in a blow, sails are pretty blown out anyway – so looking for a new set…. Have you ever seen you recommended arrangement (100-110 Yankee + Staysail ) rigged on a Hylas 49 ?

I don’t have any experience with Hylas 49, but, as I remember, the hull is based on the 1980s Stevens 47, a sweet offshore boat. Also, the underwater body is somewhat similar to our boat. Bottom line being that I think the boat will work very well set up the same way we are as a cutter.

Great article John. In TS Bill 25-35+ close reaching in the meander in Marion Bermuda this year with our brand new 9oz full dimension staysail we often unrolled our 133% #2 laminate Genoa which became a small topsail. For reaching the staysail is trimmed to the Genoa track just aft of the shrouds and the reefed jib is sheeted to the rail. As the aging #2 Genoa breathed its last just as we crossed the line at St Davids, we will be ordering a harmonious topsail for the staysail. The new adjustable Genoa cars will move to new staysail tracks on the coach roof as you suggest. Since our J42 may be slimmer at the waist than Morgan’s Cloud, could you please let us know the sheeting angle close hauled of your staysail and topsail? Some proportioning will help sighting our new cabin tracks. Cheers Bill SV ComverJence

Sounds like a plan.

Actually, on a beam to length ratio basis, MC is probably no wider that your J42. In fact she maybe narrower, at least if we use overall length for L.

Be that as it may, I don’t know the exact sheeting angle, but anyway, I think it would be a mistake just to copy our track position, particularly on boats this different. Rather, as I say in the article, get your sail designer to specify the sheeting angle. They should know since sheeting angle is fundamental to sail design.

To Geoff Skinner I have T fittings with an eye to facilitate splicing line, from Gibb via Sailing Services, Miami. You have to know the size of your socket. Fair Winds

To Geoff Skinner re: T end fittings with ring are actually by Alexander-Roberts to fit Gibb sized sockets I sourced them from Sailing Services in Miami

Thanks for fielding that.

John, (and other cutter savvy readers)

As always, a knock out interesting article that I have been pondering for some time that introduced new viewpoints that I had not considered before. For instance, the diagram that shows why the deck sweepers are such inefficient reaching sails because of the catch 22 of needing to move the sheet lead forward and aft at the same time…amazing!

I was wondering (probably along with other readers) about weather helm and tricks (sail trims) you use to reduce it on a cutter rig. We have a wonderful Brewer 12.8 with cutter rig, but I struggle to reduce weather helm when close reaching. Besides putting on some backstay tension, easing the vang a bit to allow the main to twist, and reefing the main, do you have cutter specific things you learned to help balance the boat?

Our jib is probably best described as high clewed genoa. It is a big sail, but the sheet angles are similar to that of a yankee, with the leads close to the center cockpit.

Thanks in advance. You the man! Conor

Thanks for the kind comments.

First off, have you read the above chapter (I moved your comment)? Lot’s of tips that will help.

It’s really hard to diagnose a weather helm problem without sailing on the boat, but here are a few places to look:

- What sort of shape are the sails in? If they are old and the shape has blown back, thereby tightening the leach, that will give you weather helm that is just about impossible to fix without buying new sails.

- Is the mast raked too far aft?

- Is the mast tuned so that it takes a nice fair bend ,that conforms to the main design when backstay tension is applied.

- Are the two headsail leaches nice and parallel and is the separation about equal, as shown in the shots above?

Hi John, Great article and comments. It’s amazing how little information is available about cutter rigs. I was pleased to see a picture of Mai Tai in the beginning of this article representing the cutter family. I do want to mention something that may be worth a look: Cutter rigs have two sets of spreaders on the mast to give side or lateral support to the rig at the point where the “inner forestay” attaches. The second or higher set of spreaders is where the inner forestay should attach. If there is only one set of spreaders you will have to attach the inner forestay at such a low point that the staysail area will be reduced beyond effectiveness. Running back stays should be used to prevent fore and aft pumping of the rig but they will not provide enough lateral stability to hold the mast straight when flying the staysail. So there is more to converting a sloop to a cutter than first meets the eye. Intermediate shrouds need to be added and a second set of spreaders. This means chain plates in the hull, more wire rigging, turnbuckles and two more spreaders. Personally, I would buy a cutter to begin with and forget the conversion.

Cheers from New Zealand Lane and Kay Finley

Welcome back! Even though you have just pointed out a glaring omission on my part…thanks…I think. :-).

Seriously, a very good point, although not a killer these days when so many boats have two spreader rigs.

Dear John, I have a Pan Oceanic 46 cutter designed by Ted Brewer and I am in the process of making a new set of sails for my Genoa and staysail with Lee Sails in Hong Kong. I do not have much experience sailing cutter when I bought her (SV Sunrise), her set of sails were too old (and baggy) for me to make any deductions of what to ask for in my new set of sails. I have read your post on how the 2 sails should work together and will certainly discuss that with Lee Sails. However, I do have one observation that I am not sure if it is worth pursuing to improve upon; Sunrise does not go to close haul well. The best angle with the set of baggy sails is 45 degrees with about 18-20 degrees of heel. I mentioned that I am not sure if it is worth pursuing is because many opinions I got from the internet indicates that (1) cutter are generally not designed to sail close haul as a major consideration and (2) a semi-full keel are likewise not designed for close haul. But then again, there are opposing comments (to some degree) to the above. Hence I am exploring maximizing Sunrise’s close haul ability to sail as close to the wind as much as possible with a new set of sail since I am replacing them anyway. Your views and of others sailors are very much appreciated.

One other thing I notice is that the clew on SV Morganscloud is high compare to a conventional Genoa. It is more like a high cut Yankee. I thought that it is best aerodynamicall for the clew to be as low as possible (ie decksweeper) to maximize efficiency (less spillage at the foot and low centre of pressure of the Genoa equals less heel). The clew is raised on a cruising boat to allow forward view when sailing which is owner dependent. What may be your reason for a high cut Yankee as oppose to a conventional Genoa?

Please direct me to the correct page in your website if these topics have already been discussed as I cannot seem to find them on the search engine. Thanks much,

A full read through of this chapter and the last will answer the low cut genoa issue (don’t do it). A few other thoughts.

- Nothing is going to make this boat a windward machine and 45 degrees is not bad at all for this type of boat.

- Have you considered going with a sailmaker that has a local representative in your area? Yes, I know it will cost more, but getting input from a good sailmaker is invaluable and can save you a bundle in the end by making sure you get the right sails and they work together. You will find hints about choosing the right sailmaker in the above article and here: https://www.morganscloud.com/2009/11/18/how-we-buy-sails/

- Don’t try and crowd source this decision on the forums. Many, (perhaps most) forum denizens have more opinions than knowledge. (AAC is not a forum) and it’s very hard to sort the few who know what they are talking about from the noise.

Hi John, have read the chapters. Very informative and addictive read. I should get back to work really! Ok, while preparing for the long cruising voyage (could be 4 to 7 years time) we as a family have to do with coastal sailing on our blue water cruiser. Many times the wind is on our nose and how i wish Sunrise could point higher and get there a little faster. Hence my exploration to increase the close haul performance. I can see the benefits of a true cutter for a short handed crew (basically, only my wife and I as our toddlers are a liabilities) and when the time comes for more reaching and downwind sailing arrives, I am really thinking how one can improve the upwind performance of a cutter rigged cruiser. Well, it gets worse. When we bought Sunrise, she came with a behind the mast roller furling main (Famet system which is now defunct). I know that is a very inefficient sail but a lot our sister boat owners advise against getting rid of it because of the ease of handling the main from the cockpit because the main is a big sail to hoist and handle on the conventional system. I have done some research and think that the Antal system is the way to go. But the system is expensive and I dont have the budget for it right now (including new gooseneck, reefing system etc). So I am “putting up” with the furling main until the kitty is more full but my wife thinks that I shouldnt for a short handed boat. Anyway, that is for another day. Meanwhile, I just play with the sails..

Rob: For what it’s worth, I have a steel full keel cutter with a largish staysail and a Yankee cut jib on a shortish bowsprit. I concur that 45 degrees is not unreasonable, but you can experiment with stay tensioning and certain techniques, such as backwinding the jib, to make your tacks more efficient, if not much higher. Tuning’s a bit of an art, but one well worth learning, in my view.

I just installed a Tides Marine track, full batten cars and “slippery” slugs on our new main and so far we are very pleased with the sail handling. The cost was about $1,000 for the gear, which was about 25% of the cost of the new main. You may wish to stick with the old main until you’re ready to commit. Were it me, I would change things up all at once.

BTW, how high does Morganscloud sail upwind to as a true cutter?

There’s no simple answer to that, depends on leeway, sea state and wind strength. In any sort of sea we make good about 50 degrees to the true wind angle, but at least 4 degrees of that is leeway due to our comparatively shallow draft and nothing to do with the cutter rig.

A good thing to remember when discussing close windedness is that most people lie about it, or at least are mixed up about true and apparent wind angles, or forget leeway. Almost no cruising boat, and few cruiser racers, actually make good even 45 degrees true wind angle unless the water is dead smooth. Also true and apparent wind angles on sailing instruments are almost never accurate.

Lest you thing that 50 degrees is a bad number, as the forum denizens will tell you, I need to point out that we are talking about a two time class winner of the Newport Bermuda race here.

As I say in the posts, a sloop with a low cut genoa will have better VMG in smooth water inshore. In the ocean over a multi day passage a properly tuned and sailed cutter will kick ass and take names, particularly if both boats are short handed. The key to fast ocean cruising rig is not close windedness (within reason) it’s all around speed—it’s not how fast you go that counts, it’s how often you go fast.

Even inshore, a bit of tactics counts for a lot more than 5 degrees of pointing: https://www.morganscloud.com/2010/11/04/racing-to-cruise/

Finally, there’s a simple cure for leeway and pointing too: 1200 rpm on the engine.

Hi Marc, Thanks for the advice. You boat sounds a bit like my boat except for the sails which I am about to make a decision on. I have not ventured to rig tuning yet but will do once the new sails are on. I have never heard of Tide Marine but I will check it out. The Antal system I looked at for a 46ft boat is in the region of $4000 excluding the sail!

Antal (and Harken) make fine products and on a different boat I would be happy to have them. The Tides Marine external track (which one measures with the special kit they send first) is sturdy and allows full battens and smooth dousings. It was a compromise but as we were getting an ocean-grade main, it was a logical one. Be prepared to grind your slug gate a little larger, however, should you choose to go this route. You may find this and the links off it instructive: http://alchemy2009.blogspot.ca/2016/05/sticking-around.html

Lastly, if you are tuning in earnest for the first time, remember to check and snug up your chain plate bolts first and to take it easy and to get a racing sailor aboard to help. Employ rum if needed.

I think your boat may be a bit big for the Tides system. A good mainsail slide system is a true blessing. Might be better to save up for a good one than cheap out.

Hi John, yes you are right. We close haul at 45 degrees to apparent wind. The one that is indicated on the Raymarine dial. Our system isnt wired (yet) to indicate True wind to us. Therefore we use the apparent wind angle as an indicator because when the boat moves, it is the wind angle that she sees. About Sailmaker. I live in Singapore and we do not have a local sailmaker here as the sailing community is not big enough. Lots of powerboats. Lee Sail in Hong Kong is just about the nearest and I was about to make a decision on a lowish cut Genoa until I read your posts. Our boat was designed as a true cutter and at one time i wanted to convert her to a full sloop for better upwind sailing. I am now doing a lot of rethinking and rereading your posts…

I have a low-cut genoa for strictly light air, but the standard sail is a high-cut Yankee. It is very versatile and only starts to get useless when 50% rolled up or so. The staysail can, if desired, have a set of reef points put it for truly hairy conditions. Some prefer both jib and staysail to be on furlers; I prefer the bulletproof (to me) hank-on staysail and storm staysail. With these two, we can run off in 50 knots. The trick to loving a cutter is to sail it in all weathers. Then you learn its qualities and forget stuff like the big old tacks you have to make.

OK, I see why you are so worried about this. 45 degrees to the apparent wind will equate to around a 120 degree tacking angle, and that’s pretty bad. First step, is, as you have determined, new sails. That and decent tuning should get you at least a 20 degree improvement in tacking angle which will be a huge improvement in VMG.

Good spotting, John. I thought he meant 45 degrees either side of the true wind, meaning a 90 degree tack, or close reach to close reach, I suppose.

Hi Marc and John, thanks for the advice. Will discuss Yankee jib and a low cut staysail with my sail maker and see what they come up with…

Hi John, I am working on my new sail in earnest. Can you explain what do you mean by ” the staysail stay should be parallel to the headstay and set about 30% of the foretriangle base (J) back from the headstay.” My boat’s main sail is a behind the mast roller furling sail with batten and has a straight leech. I know it is not an efficient sail but offer the convenience not getting out of the cockpit on a shorthanded boat. On its own, it does not give much forward speed to the boat. Say for a 10 knot wind, the boat moves only 3 knots (assuming no current). The genoa was the main driving force. Now, if I were to go for a Yankee jib and staysail combo, how do I get them right to compensate for an inefficient main. Bigger sail area?

I explain all of that in the three chapters on cutters.

Hi John, ok, thanks. Rob

Hi John, I am about to make a purchase of my Yankee jib and staysail. For the staysail Sail maker recommended a 9.4oz cross cut furling Dacron (10.76m luff x 3.9m foot x 9.6m leech). I think that should be ok as it is not a very big sail. The Yankee is a bit tricky because I am deciding on the cut and material. Sail maker recommends a 8.8oz cross cut furling Dacron (15.45m luff x 7.6m foot x 12.09m leech) or a tri-radial cut 9.1oz USwt Challenge Warp Drive dacron(WD9.11). The tri-radial cut is 50% more expensive than the cross cut option. I know you mentioned that the tri-radial cut is the way to go but my reservation is on the material (which I have not heard of anyone who has used it before) and a first timer converting to a true cutter sail plan and of course the cost. How much different in sailing performance is there between the cross cut and tri radial cut?

When I make a recommendation in a chapter like this I have thought about it a lot and it’s my recommendation. It would only change in light of new technology. I don’t believe this to be the case here.

My understanding is that the differences in cut distribute the sailing forces differently across the sail. The weight and strength of the material (is “Warp Drive” equivalent to “HydraNet”, which is Dacron beefed up with Ultra-PE?) is a separate metric. I went with a fairly robust weight of regular Dacron for my new main because of my reefing habits; my cutter’s Yankee is also stock Dacron, but were I to replace it, I would opt for a tri-radial cut as I suspect you can reduce stretch and bag over time. Me, I prefer a lighter cloth for the Yankee and an earlier furl.

If you don’t have money for the more expensive sail, moderation of your sailing habits to more conservatism is the cost of keeping the sail an equal number of miles at sea, I would think.

I have a bit more time today. I have no experience with warp drive, but I can say that laminates are now pretty reliable, so I would not worry too much about that. Also, it’s important to realize that with sails, like many things, initial cost and cost of ownership are two different things. So, while a crosscut woven Dacron sail may seem cheeper I have often found that a radial cut laminate sail keeps it’s shape so much better that in the end it can be a more economical choice.

In addition you will have more fun sailing your boat with a better sail.

Bottom line, cross cut is simply wrong for high cut jibs. In fact, even back in the day when I was sailmaking, long before radial cut headsails, we used to miter cut high cut sails for just this reason.

Hi Marc, very sound advice. Yes, I must admit that money is not on my side with so many things to do on the boat plus a family. I would like to go for a Dacron tri-radial cut but my sail maker does not do a Tri-radial cut with the standard Dacron. He would use laminates of Wrap Drive. But there is so little that can be found on Wrap Drive on the internet. Is it as good as the Hydranet? (my sailmaker does not use Hydranet, only Challenger material I think). So, is Wrap Drive worth the 50% increase in price? Not a question to you but to myself. But I appreciate the spirit of your honest sharing. Cheers mate,

Hi John, interesting that you mention that laminates are “pretty reliable”. All the feedback I got is to steer clear from it as it has a life of at most 5 years plus all the problems with mild dew. The only sailors I know who uses them are racers. In fact I do not know of any cruiser who uses laminates. Most use standard Dacron and Hydranet. Wrap Drive is not a laminate but Dacron with “wrap yarn” (whatever that is) to perform like laminate. I am uncertain of the maintenance requirements/issues, ease to repair and durability of the material to really make an informed decision. I think it is too new in the market. And yes, point taken on the tri-radial cut for a Yankee.

Leech line. most times it is difficult to reach the clew to adjust it while sailing. How does one do it on a Yankee which has an even higher clew. A friend of mine suggested using “over the Head” leech line where the lines goes over the head of the sail, comes along the luff to the (near) tack. It has a small block at the head to facilitate the acute turn of the leech line at the head. Have you had any experience or comments on this system of leech line?

As I said, I have no experience of Warp Drive, but after having a quick look it looks like a competitor to Hydra Net. Anyway, you have my opinions. Be aware that most forum denizens just repeat mythes, so making buying decisions based on “accepted wisdom” on a forum often leads to tears. Before Hydra Net was available, I used laminates for cruising and racing for years and had good service. If you are cruising full time, 5 years can be good, not poor service, it all depends on the miles. I generally find that a well made set of radial cut sails will last about 30,000 miles before losing their shape to the point I can no longer stand to sail with them.

And yes, leading the leach over the head is the required for a high cut sail, and something that any decent sailmaker should do as the default.

Hi Marc, this is from Curisersforum : “Warp is pretty much a marketing play to get you to pay 40% extra for a dacron sail. It’s still simply a woven dacron cloth and it will stretch on the bias just like any other (good tight weave) dacron cloth. In no-way will it perform (low stretch) like a laminate cloth.

There have been numerous attempts to make a woven dacron that is strong in one direction into good sails and they have all failed. Using Pentex fibers (a high modulus dacron) in one direction was all the marketing a rage a while ago. However, ALL woven cloth will stretch on the bias (that is at 45 degrees across the weave) no matter how low stretch the fibers or un-crimped the weave is. This is just a simple fact of the physics of weaving. And this is true if its cross cut or tri-radial. These attemps have tended to produce sails with shorter longivity than regular dacron cross-cut (because they try to use the low stretch in one direction and overload the bias direction).”

I guess the best advice is from someone who has actually used it.

Hi John, Thank you for taking the time to read into Wrap Drive. I really didnt expect you to as you already have a lot on your plate looking after your website. I was hoping perhaps some sailors in this discussion would have some experience. I am taking your opinions and advice thus far very favourably and seriously. Cheers,

Hi John, sunstrip protection for sails. Do you have any experience of using Challenge UV150 and Sunbrella as sunstrip for the Yankee and staysail? Of course in terms of performance, it is preferred not to have any sunstrip at all as it leaves the trailing edge of the sail relatively smooth. But in the tropics, some protection is needed. There is another option of using a laced up “sock”. But that needs another halyard plus more fabric to stow… And advice would be most appreciated. Thanks,

I don’t like Sunbrella for a sunstrip; too heavy so it distorts sail shape. Our sailmaker uses a self-adhesive product that works well and adds very little weight. I’m not sure what the product name is, but your sailmaker should know.

I am refitting a 1990 Cabo Rico 34 cutter with new sails and have been advised by my sailmaker that a 135 jib top “will give her more power up wind” whereas my internet research into the few other CR34 cutters that I could find shows those boats have anywhere from 110s to 130s for the jib top. Do you have an opinion on the 135 versus a smaller sail? And radial versus cross cut? I am also converting the staysail from hanked on to roller furling and dispensing with the boom. Any reason to consider retaining the boom as opposed to free footing the staysail? Of course I want to retain good self tacking ability as I single hand a lot. Thanks for a great website/resource.

If you are going to sail her as a true cutter using the Jib Top and staysail together any time the wind is forward of the beam, in my opinion, it would be a major mistake to build the jib top with that much overlap. I detail the reasons in these three chapters on the cutter rig. If you want more sail for light air performance buying a light air sail like a code 0 is almost always a much better solution than trying to add a bunch of area to the jib top.

Does your sailmaker clearly understand that you are planning to sail her as a true cutter with both headsails in use at the same time?

Cutter-Rigged Sailboat Definition: Everything You Need to Know

by Emma Sullivan | Aug 12, 2023 | Sailboat Lifestyle

Short answer cutter-rigged sailboat definition:

A cutter-rigged sailboat is a type of sailing vessel characterized by its rigging configuration, which includes a single mast set further aft and multiple headsails. This design offers versatility in various wind conditions, providing better control and balance while sailing.

1) What is a Cutter-Rigged Sailboat? A Comprehensive Definition

A cutter-rigged sailboat is a versatile and elegant type of sailing vessel that offers sailors a range of benefits and capabilities. With its distinctive rigging setup, the cutter sailboat has long been favored by sailors for its maneuverability, stability, and ability to handle different wind conditions. In this comprehensive definition, we will delve into the intricacies of the cutter rig and explore why it remains a popular choice among sailing enthusiasts.

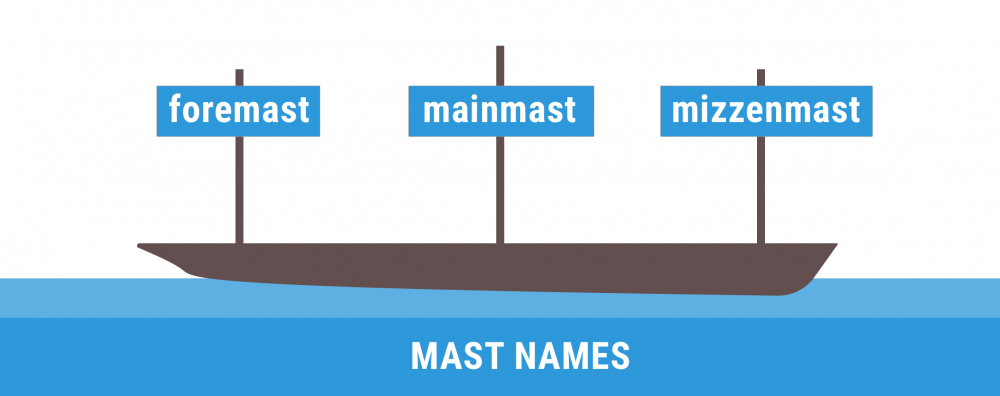

At its core, a cutter-rigged sailboat features a specific arrangement of sails and mast configuration. Unlike other types of rigs like sloop or ketch, a cutter possesses two headsails – both the jib and staysail. The jib is usually larger and set forward to catch the main flow of wind, while the staysail sits between the foremost mast (known as the foremast) and the mainmast. This arrangement provides maximum control over different wind speeds and directions. While some smaller cutters may have only one mast, larger vessels often boast multiple masts, creating an impressive silhouette on the water.

One of the main advantages of a cutter rig is its versatility in handling various weather conditions . The combination of a large jib upfront with its increased surface area allows for heightened propulsion when sailing downwind or with favorable winds behind you. On the other hand, when facing challenging upwind conditions where close-hauled sailing is required, a smaller but easily controllable staysail comes into play. This dual headsail setup gives sailors better options for optimal sail configurations depending on wind angles – an invaluable feature that makes cutters ideal for long-distance cruising or racing.

Additionally, stability plays a crucial role in determining why many sailors opt for cutter-rigged sailboats . With two headsails set in front of your boat ‘s centerline but balanced proportionately around it, there’s less chance of being overpowered by strong gusts or unsteady winds compared to single-headsail rigs like sloops. This inherent stability allows for better control and reduces the risk of a sudden broach, which can be particularly crucial when sailing in harsh or unpredictable conditions.

Not only does the cutter setup provide superior handling, but it also enhances safety on the water. Since the staysail can easily be brought down or adjusted independently from the larger jib, sail changes are more manageable and less physically demanding for crew members. This flexibility is particularly vital during challenging weather conditions, as it minimizes time spent on deck in potentially dangerous situations .

Beyond its functional advantages, there’s an undeniable aesthetic appeal to cutter-rigged sailboats that captivates sailors and admirers alike. The imposing presence of multiple masts adorned with gracefully billowing sails creates an aura of classic beauty that pays homage to traditional sailing vessels of old. Whether cruising leisurely along coastlines or partaking in thrilling racing competitions, a cutter’s stylish design ensures you’ll turn heads wherever you go.

In conclusion, a cutter-rigged sailboat is a comprehensive embodiment of functionality, style, and adaptability on the water. With its distinct two-headsail setup providing excellent control across varying wind conditions, it stands out as an ideal choice for serious sailors seeking an enhanced sailing experience. From its versatility to stability and safety benefits – not to mention its timeless elegance – no wonder cutters remain cherished by seafaring enthusiasts worldwide who appreciate both tradition and innovation in their voyages.

2) Understanding the Cutter-Rigged Sailboat: Definition and Characteristics

Are you a sailing enthusiast looking to explore different types of sailboats? If so, then understanding the cutter-rigged sailboat is essential. This unique and versatile vessel has its own distinct features and characteristics that set it apart from other types of sailboats . So, let’s dive into the world of the cutter-rigged sailboat , exploring its definition and noteworthy qualities.